11 November 2018 — By Eddy Smythe, Alwyn Collinson

J Smythe: The Second World War navigator & his Windrush story

From being one of the first Black airmen in the RAF, to being in charge of the historic voyage of the SS Windrush, Johnny Smythe led an extraordinary life.

Pilot officer Johnny Smythe in training. Smythe RAFVR being instructed in the use of the sextant by a flying officer instructor.

By any measure, John Henry Smythe led an extraordinary life. He was one of the first Black airmen in the Royal Air Force. The man in charge of the historic voyage of the SS Windrush. A Krio who said that his skin colour saved his life when he was captured by the Nazis. London Museum spoke to his son, Eddy Smythe, about his father’s amazing experiences.

Eddy, like his father, was born and brought up in Freetown, Sierra Leone. He has lived in Britain since 1976 and is an expert in his father’s extraordinary life story: “He joined the Royal Air Force [RAF] in 1940, at the height of the Second World War. Sierra Leone was a British colony and was asked to put forward six young men who would be trained as pilot. My father was one of hundreds who applied. Sierra Leoneans knew the importance of beating Hitler and the Nazis.”

Fighting in the Second World War

Johnny Smythe was selected to train as a navigator, due to his high scores on mathematics tests: a testament to the high standard of education in Sierra Leone at the time. He successfully navigated 27 bombing missions over Germany. Many crews lasted less than 12 operations, killed or captured when their aircraft was shot down.

In an interview with London Museum, Eddy says, “It was a difficult and scary time; every mission was terrifying. You never got used to be being shot at. Obviously, successfully flying 27 missions, Johnny was considered to be very, very lucky. A lot of his fellow airmen felt that he had some sort of aura around him, they were keen to fly in his plane. They used to call it black magic, and he played up to that.”

Despite his fascinating experiences, Eddy recounts that his father didn’t tell his children anything about the Second World War for many years. He remained deeply affected by the last two years of the conflict, which he spent in a prisoner of war camp. He had been shot down on a bombing mission over Germany, on 18 November 1943.

A group of African and Caribbean Royal Air Force officers, around 1942. Johnny Smythe is bottom row, second from right.

“No matter how quiet or gentle you were, he woke up with a scream”

Eddy Smythe

Eddy shares, “When he came back to Sierra Leone, he threw out his uniform and the logbook that he kept in the prisoner-of-war camp: he just did not want to engage. Growing up in the early 1970s, my brother and I were fascinated by the Second World War, we bought magazines and watched films but he wouldn’t talk about it.

“There were some signs: the one thing I do remember is that he found it very hard being woken up. If we had to have someone wake him from sleep, we used to have to draw straws for who would do it, because no matter how gentle or quiet you were, he woke up with a scream. He was almost lifted off the bed by that scream. We recognised that as a throwback from the war.”

Johnny didn’t start to talk about his wartime experiences until the end of his life.

Johnny Smythe in his RAF uniform.

“Two or three years before he died we started to pester him to tell us about the war. I got him to talk about what happened just before they were shot down over Germany: the plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire, he was wounded twice, once in the ribs and once in the groin. But they continued to the target and dropped their bombs. Normally, the plane would then climb as high as possible, to get away from danger, but one of the engines had been damaged. So they were shot down by a German fighter plane. He managed to jump out of the burning plane.”

Johnny was captured, despite an attempted escape on a stolen bicycle and hiding in a barn. He gave himself up after German soldiers raked the building with machine-gun fire. Eddy says, “After he was captured and taken to the local German police station, there was one officer who kept hitting him, smacking Johnny with the butt of his rifle, in the ribs where he’d been shot. That memory made him angry.

“At that stage he said: ‘Right, I’m going to be shot anyway. This officer is a little man, but I’m 6 ft 4 in. He said, the next time this German comes near me, I’m going to grab this guy and snap his neck, before they can kill me.’ He would have done it, too. But the little German never hit him again.”

“I'm fighting for my king”

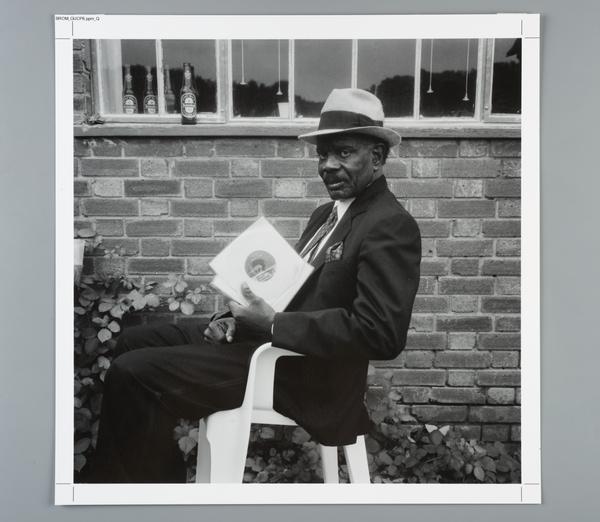

Johnny Smythe, when in Stalag Luft

Prison camp, and the end of the Second World War

So, was he treated differently because of his race?

Eddy says, “I think the Germans were just astonished to see a Black man in an RAF uniform. They said: ‘Why are you here? We’re not fighting Africa.’ But Johnny had his answer ready: ‘Sierra Leone is part of the British Empire and I’m fighting for my king.’”

Johnny was taken to the notorious Stalag Luft I, a prison camp for Allied airmen captured by the Germans. Life in a prisoner of war camp was “bouts of extreme boredom littered with bits of incident. It was a long, hard two years until 1945, when the Red Army liberated Stalag Luft I. The camaraderie of his fellow airmen kept Johnny going: ‘We were all just prisoners together. It wasn't until I looked in the mirror that I remembered that I was Black.’”

“They had access to the radio, they had a chap who could put one together with a few wires so they knew what was happening outside. They knew that the Russians were coming from the east. One day they got up in the morning and the guards were gone. The Germans had just left in the night: they didn’t want to be captured by the Russians and they didn’t want to be left with the freed prisoners.”

The Empire Windrush ship in dock at the Port of London.

An officer on SS Windrush, and life after

After the end of the war, Johnny Smythe made history in 1948 as a key figure in the story of the SS Windrush, marking the beginning of a rich period of Caribbean immigration to Britain.

“He was the senior officer aboard the Windrush; he was in charge of taking young men from the colonies, who had served in the forces, back home after the war had ended.” But confronted by high unemployment in Jamaica, most of the passengers asked for permission to return to Britain. As the man on the spot, Whitehall asked Johnny to decide whether to bring them to the UK.

“My father didn’t realise that this was such an important matter. Not until he got back to Southampton and they were met by a reception committee, had planes flying past, did he sense that he had made a very important decision.

“My god Johnny, I shot down a British bomber that night”

German ambassador

After leaving the armed forces, Johnny Smythe trained as a barrister in London, returning to an eminent legal career in Freetown. He rose to become a Queen’s Counsel and Attorney General of Sierra Leone.

“We are obviously a culture rooted in slavery. The thing with the Krios is that they’re not indigenous Sierra Leoneans. Culturally, they never looked inwards to Sierra Leone, they looked out across the Atlantic to England. They were driven to achieve, to be the best, educationally and professionally – I think my father was in that camp.”

Despite his experiences in the war, Johnny Smythe harboured no bitterness towards the Germans, seeing them as soldiers who served their country, just the same as he did.

Eddy: “He had one fascinating meeting, years after the war, when he had a successful legal practice in Sierra Leone: he was at a cocktail party at the British ambassador’s residence in Freetown, where he ended up talking to the German ambassador about the war. When told about the date and place that Johnny was shot down, the ambassador turned pale: ‘My god Johnny, I got my first kill on that day, I shot down a British bomber.’ They put their arms around each other and were almost in tears.”

Alwyn Collinson is Digital Editor at London Museum, and Eddy Smythe is Development Surveyor at Smythe Associates, and son of Johnny Smythe.