06 October 2016 — By Sally Brooks

Is this burnt bible a survivor of the Great Fire of London?

A charred bible, hidden away for years. Could it be a survivor of the Great Fire of London? Our Librarian’s journey to uncover its secrets spans centuries, from a 1608 printing press to modern forensic techniques.

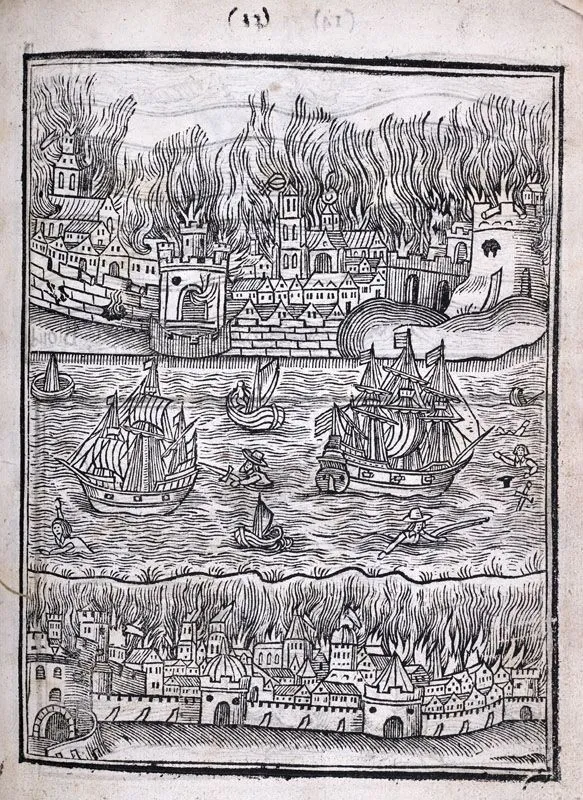

Print from 'Monarchy or no monarchy in England', 1651. The book, by William Lilly, predicted a great fire that would destroy London.

Our collection has a wealth of information and objects related to the Great Fire of London, including a number of books from the museum's library. Most of these books are good, sound texts, collected and donated to us by author Walter George Bell (1867–1942).

But there was an item about which we knew virtually nothing. This had been languishing unappreciated in a cupboard for quite a long time, till 2016 when the museum organised the Fire! Fire exhibition.

The object in question was a very badly damaged bible.

The pages of this bible showed signs of fire damage at the edges, while the text block had slumped from the binding. That suggested that the bible had been very wet at some point in its life. Perhaps, doused to put out the flames. Its label offered few clues but suggested that it might be related to the Great Fire.

With a chance to put this on display in the exhibition, and solve a puzzle within our collection, I decided to spend some time to investigate its mysteries.

Where did the bible come from?

The first place to look was the bible’s history – who had given it to the museum, and what evidence had they left us? The only available clue to its provenance was a label attached to the front cover, which says: “Cheltenham Coll. Museum. Bible from the Fire of London (in 1666). Presented by Mrs. Walker”. And so, Cheltenham was the first place to look for information.

I contacted the very helpful Cheltenham College archivist, Christine Leighton. She found an entry in the accession register stating that a Mrs Walker from South Kensington had donated a “Bible from Fire of London” on 14 October 1870. Christine explained that the college’s varied collections of artefacts had been boxed up during the Second World War, and were never unpacked or put on display again afterwards.

In the 1970s, much of the material was distributed to other museum collections. Documents at Cheltenham suggested that the burnt bible was one of several items that went to Merseyside Museum in May 1976. However, National Museums Liverpool was unable to confirm this, and so the trail of how the bible came to be in a bookcase at London Museum went cold.

The bible's cover, with label attached.

Tracking down ‘Mr Harding’

One tantalising connection comes from London Museum’s first director, Tom Hume. He joined in 1972, having previously been director at City of Liverpool Museums. For the staff at Liverpool, the newly opened London Museum managed by an ex-colleague would have been the ideal place to send a Great Fire of London item.

The only other clue to the book's history is a faint pencil inscription inside the front cover, which says: “This Bible was at Mr Harding St Martins Lane in the Fire of London”.

We first thought that this referred to the bible’s owner at the time of the fire. But our Curator Meriel Jeater found no mention of a Mr Harding in the City’s 1666 hearth tax records, or any other sources.

It took Christine to point out the obvious to us, that this inscription might not relate to 1666 but might be later. In fact, it could well refer to Samuel Harding, a bookseller dealing in bibles who had a shop in St Martin’s Lane in the 1700s.

The written inscription on the inside of the bible.

Unravelling the mystery: A pre-Fire London bible?

So much for tracing who had owned the bible in the past. It got me no closer to my real concern: Did this book really pre-date the Great Fire of London, or was that information just a family myth, passed down to Mrs Walker and on to Cheltenham College when she donated it in 1870?

Dating a printed work is usually a fairly straightforward task, with details such as title, author, publisher and date being printed either on the title page or, for older material, as a colophon at the back of the book. However, the bible was missing many pages at both the front and back and the surviving pages were charred and in poor condition.

When you need help with a book, the obvious source is an expert at the British Library. From a few photographs Tim Pye, Curator of Printed Heritage Collections, immediately recognised our poor specimen as a Geneva Bible of around 1610. In a few emails, he picked out vital identifying details hidden within the book.

The bible's spine, showing repairs to leather cover.

Hidden clues in the bible’s pages

The first are the chain lines – faint watermarks left on the pages from when the paper was first made. In the 17th century, paper was made by hand. A worker would dip a wire sieve into a vat of linen pulp, then pull it out and shake the pulp into a flat sheet. As the linen dried in the sieve, the wire would leave faint lines on the new sheet of paper. These chain lines are part of a book’s DNA, helping to discover how it was assembled.

Next were the signatures, small marks made on the sheets by the bookbinder who assembled the bible. From these clues, Tim was soon able to identify our bible as having been published in 1608 by Robert Barker. It looked like it might have survived the Great Fire of London after all.

So, what does all this tell us?

From an undocumented, undated and badly burnt bible, we now know that it was published in London in 1608 and that, at least as far back as the 19th century, it was cherished as relic of the Great Fire of London.

It was possibly in the possession of a London bookseller in the 1700s, and by 1870 it belonged to the Walker family and had made its way to Cheltenham College. From there, it probably went to Liverpool in 1976 and onwards to London Museum.

We will never know with absolute certainty that the bible was burnt in the Great Fire of London, but it seems highly probable. However, even if its history turned out to be an 18th or 19th century fraud, the bible is still an evocative item.

Sally Brooks is Librarian at London Museum.