26 January 2022 — By Beverley Cook

Hidden stories behind everyday tickets

Who saves a ticket? Well, as a museum, we’re glad some people do, and for Curator Beverley Cook, it's fascinating to look beyond the ‘throw away’ initial purpose of the tickets to reveal their rich back stories.

Within London Museum’s printed ephemera collections can be found a vast array of tickets of every description. As classic ‘throw away’ items, usually discarded once they have fulfilled their purpose, tickets are a perfect example of the recognised definition of printed ephemera as “the minor transient documents of everyday life”.

So, how and why does the humble ticket so often find a permanent home in social history museums?

Many tickets in our collection were retained by the original holder, often for many years, as a material reminder of a personal memory or momentous event, and subsequently offered to the museum to ensure preservation of both their physical and contextual significance. As a museum with an extensive printed ephemera collection, it is our role to look beyond the ‘throw away’ initial purpose of the tickets to reveal their rich back stories and showcase their potential to offer a fresh – and often unique – interpretation of London’s social and cultural history.

Here are some tickets in our collection with interesting stories of what they tell of London and Londoners.

From pawnbrokers to Victorian public baths

It’s a great joy to discover, within our collections, rare material evidence of working class life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The following tickets perfectly represent two common activities often associated with London’s poor – the pawning of goods and public bathing. On closer inspection, however, these tickets also reveal a more complex narrative of working class life in the early 20th century that differs from the imagined Dickensian vision of London as a city divided between rich and poor.

Ann Simpson’s pawnbroker’s ticket from January 1908.

The pawnbroker's ticket refers to the pawning of a “gravy spoon and 6 teaspoons” by Ann Simpson, who lived at “33 Mina Road” not far from her pawnbroker’s premises in Old Kent Road.

When Charles Booth published the third edition of his extensive Inquiry into Life & Labour in London in 1902–1903, he identified Mina Road as "fairly comfortable" with residents having "good ordinary earnings". Many living in this and the surrounding roads worked in City offices or were skilled tradespeople, not, therefore, the lowest labouring classes traditionally associated with regular visits to the pawnbroker to "cash in" their meagre belongings.

Ann’s ownership of a set of spoons also suggests she was not one of London’s poorest citizens. However, this is one of several pawn tickets in the collection issued to Ann in 1908. Unfortunately, we don't know why Ann needed to pawn her possessions, but perhaps her personal circumstances changed around that time leaving her struggling. For Ann, like many fellow Londoners of all social classes, the local pawnbroker was a welcome source of cash when times were hard.

The public bath ticket similarly reveals the complexity of London’s class system in the early 20th century. By 1912, when this ticket was issued, local borough public baths recorded over 3 million annual visits, with more facilities for men than women.

This ticket entitled the holder to a "first class warm bath" in the men's section of the Greenwich public bath house. The baths were enclosed in separate cabins with a seat, hooks for clothing and sometimes a strip of carpet, mirror and brush and comb.

As described by George Sims in his 1903 series Living London, the “first class” bathing area also usually included a comfortable waiting room with a fire and supply of newspapers. Rather than being a ‘hang out’ for Dock workers and labourers, these waiting rooms often took on the air of a men's club with regulars meeting weekly to discuss politics and business.

Suffragette struggles: Contrasting perspectives through preserved tickets

Many tickets in our collection include handwritten annotations by the holder that are often more significant than the ticket itself. On first glance, an interesting aspect of this ticket is that it admits a ‘man’ to a meeting organised by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), which did not allow male members.

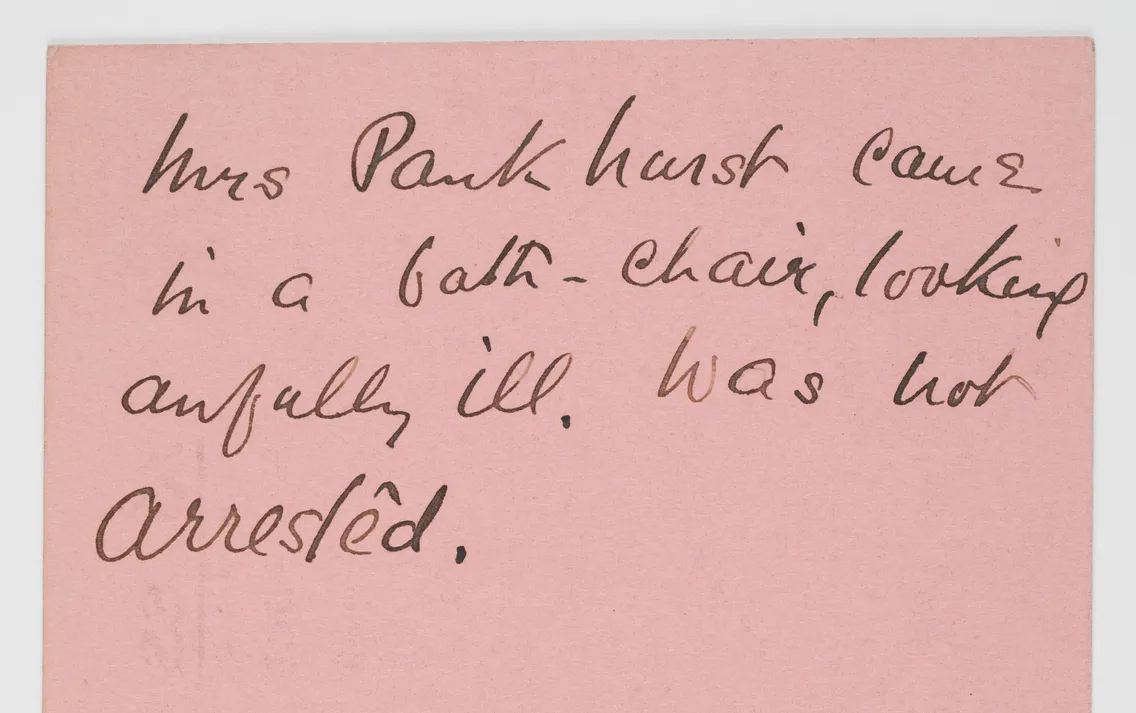

However, it is the handwritten note on the reverse that makes this ticket a unique record of a significant event. “Mrs Pankhurst came in a bath-chair, looking awfully ill. Was not arrested.” Such simple words, but how powerfully they reveal the shock of the ticket holder as WSPU leader Emmeline Pankhurst, temporarily released from prison and visibly weakened by hunger strike, made a dramatic appearance at the meeting.

Pankhurst was serving a three-year sentence at Holloway prison for inciting persons to place an explosive in a building. She was repeatedly released under the 1913 Cat and Mouse Act when her life was in danger from hunger strike. Public appearances usually led to her re-arrest but not on this occasion.

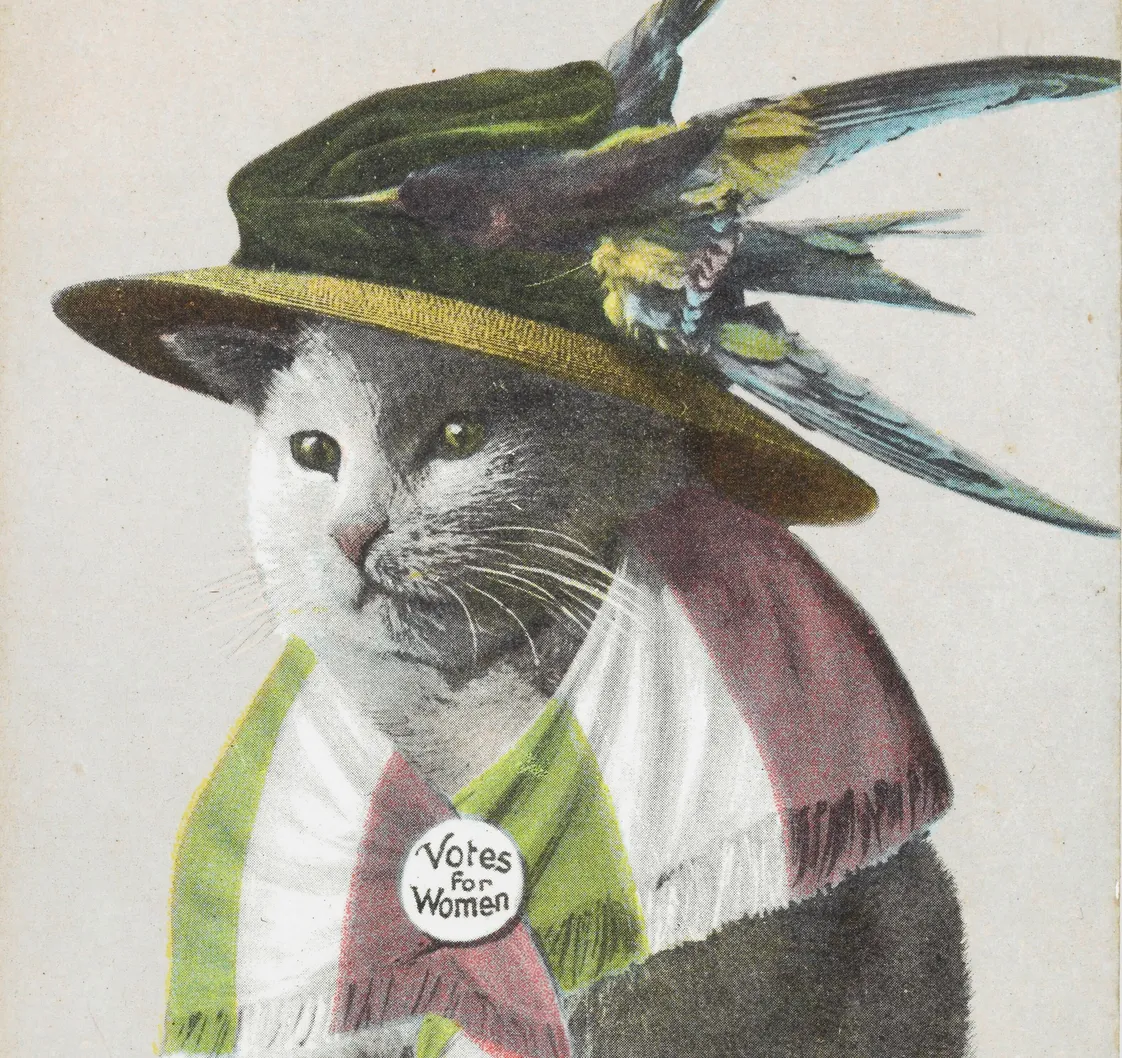

The drama of this meeting occurred at a time of growing public intolerance towards the militant tactics of the Suffragettes that included arson, bombing and window smashing as represented on the crest of this spurious membership card for the Society of Disunited Militant Suffragettes. The commercially produced item was purchased in London from a penny street trader just two months before the meeting of July 1913, and offers a satirical and typically misogynistic view of the campaigners, claiming “the membership card entitles the holder to neglect her domestic duties”, and “The bearer of this ticket is called a Suffragette who tries her best the sexes to reverse”.

Such condemnation of the campaigners as having abandoned their traditional feminine roles was not unusual and this ticket offers a perfect counter-balance to the WSPU meeting ticket.

Retaining mementoes: Wellington's funeral pass

Rarity in the world of printed ephemera often has little bearing on the financial value of an object. However, a rare ephemeral item that has been kept by chance rather than be thrown away, and subsequently donated to the museum is always a matter of joy.

One of these ‘rare’ survivals in the collection is this “Inhabitants’ pass ticket” issued to residents living along the route of the Duke of Wellington’s funeral procession in 1852. The ticket enables the holder to pass through the barriers, on foot, to their home in Ludgate Hill.

Wellington’s military leadership in the Napoleonic wars ensured his status as a national hero and his spectacular state funeral procession brought London to a standstill. Unfortunately, there is no documentary information to understand why the holder decided to retain his pass, but perhaps retaining this as a souvenir enabled them to ‘feel they had played a part’ in this momentous event in history.

From World War II to modern London life

Tickets often provide a snapshot of a moment in history that appears remote and disconnected from contemporary life. These two tickets issued to A. Epstein for permission to shelter in both the London Underground and a public shelter during World War II air raids represent the resilience of Londoners as they endured the fear of nightly bombing raids unimaginable to us today.

But equally significantly, the tickets also reveal the planning and measures taken by the authorities to keep its citizens safe but orderly during difficult and fearful times. War introduced restrictions previously unthinkable in peacetime and also enhanced government intervention in the day to day life of Londoners.

The relevance of these tickets to our life after the Covid-19 lockdowns is stark, reminding us all that the pandemic was not the first time Londoners' movements were controlled by rules and regulations.

Despite their humble origins tickets that find their way into museum collections offer a rich research resource for social historians. It is a privilege to care for this wonderful collection with so much potential to inform, delight and surprise.

Beverley Cook is Curator, Social and Working History at London Museum.