22 December 2022 — By Finbarr Whooley

Handkerchief politics: The Irish Question

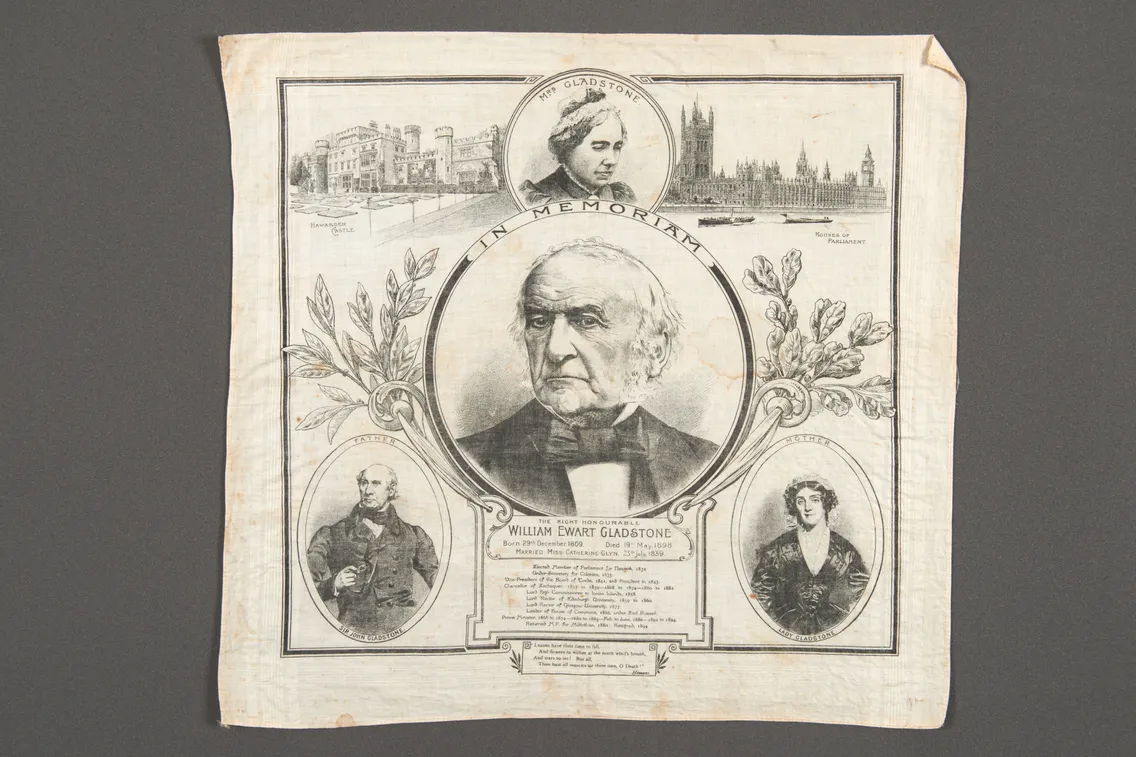

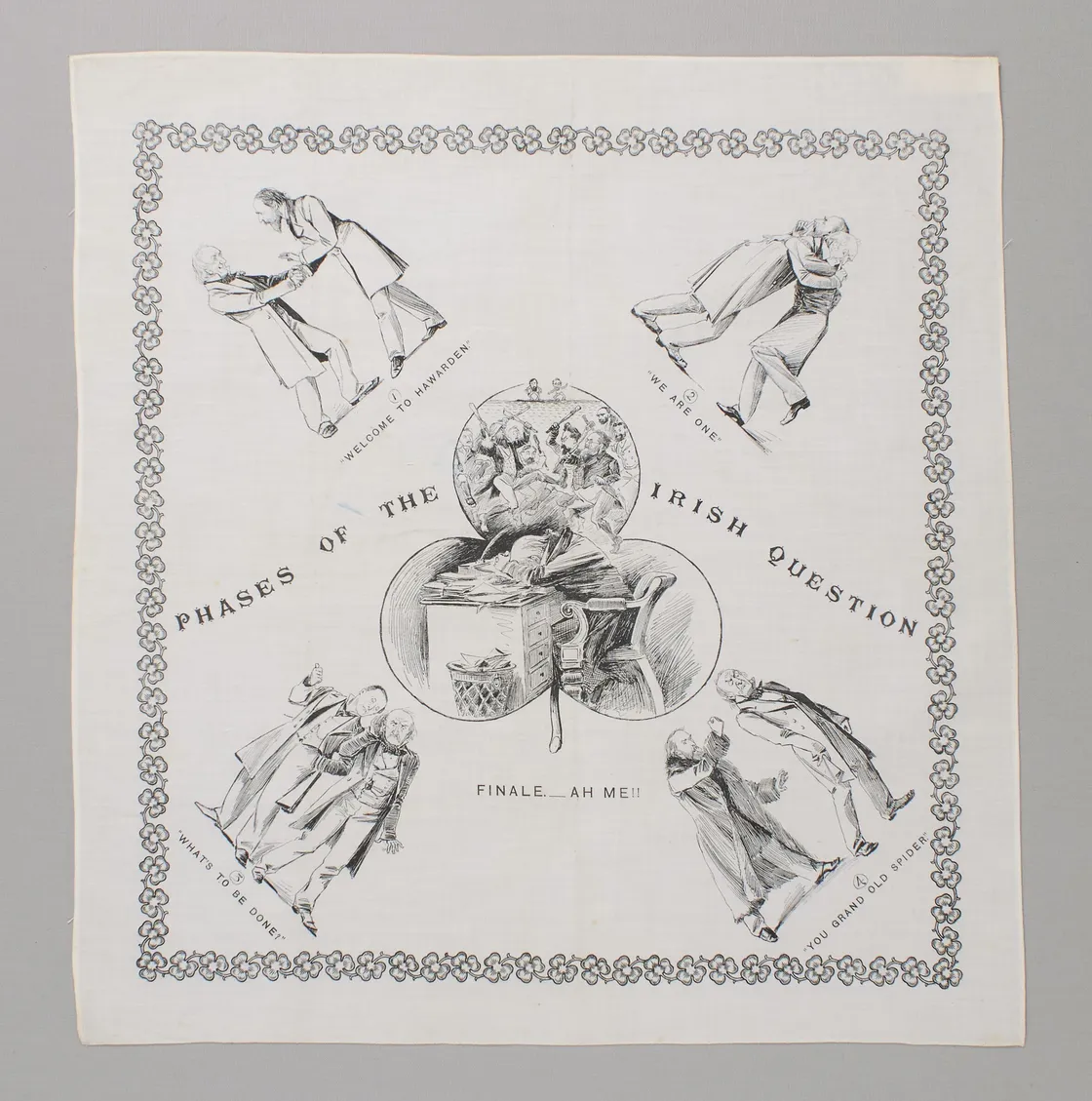

A satirical handkerchief in the museum’s collection highlights both an interesting phase of British politics in the 1880s, as well as a quirky, male fashion statement.

Significance of satirical handkerchiefs in politics

It’s probably not the first use that comes to mind, but in the 18th and 19th centuries pictorial handkerchiefs had increasingly become a satirical subject matter – chiefly in the male sartorial domain. As a result, gentlemen could display their political persuasion or sense of humour through their choice of handkerchief. These were not hidden away in pockets, but displayed with élan, hanging from coat pockets.

The museum holds an intriguing collection of handkerchiefs with political messages. This seems unusual today, but in Victorian London, most people owned handkerchiefs. They were relatively inexpensive because cotton came cheaply from the Empire and industrial techniques such as engraved copper roller printing allowed handkerchiefs to be produced in bulk.

They follow in a tradition of political posters and broadsheets that were popular in Georgian London, where great events of the day were often discussed and satirised.

Historical examples of political handkerchiefs

Take, for instance, one of the handkerchiefs from the museum’s collection, from the late Georgian period. It satirises a visit by King William IV and Queen Adelaide to the City of London for the Lord Mayor's Banquet in 1830. Cartoons of the period were often very rude, and in this example, John Key, the Lord Mayor elect, was represented as a donkey.

Another handkerchief in our collection opens a window on a period in British parliamentary history when the so-called “Irish Question” was the key political topic of the day, and one that forms the centrepiece of this article.

Home Rule for Ireland

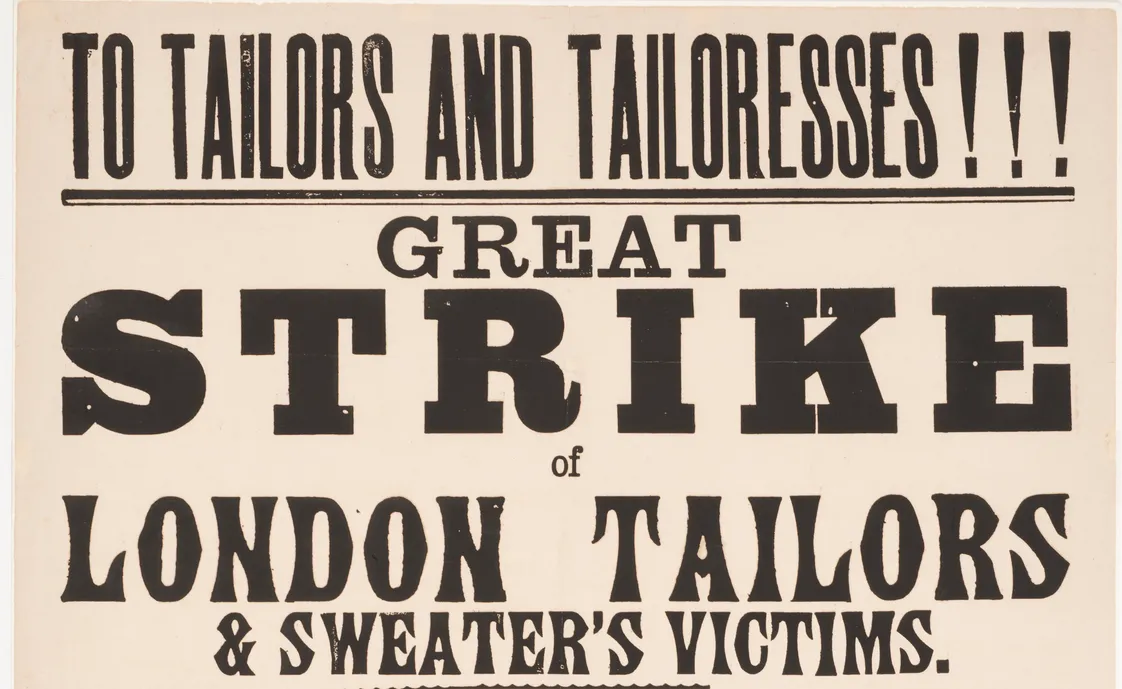

In the 1880s, the Irish Parliamentary Party also known as the Home Rule Party had about 80 seats in the Westminster Parliament.

At this time, the British Empire was arguably the most powerful superpower on earth. The politics of the day was dominated by imperial issues, including the relationships with Russia, India, Africa, Australia and Canada. The two great political parties in Westminster (Liberals led by ‘the grand old man of British politics’ William Gladstone and Tories led by the popular Lord Salisbury) were very evenly balanced, and the Irish party sometimes held the balance of power. As a result, Irish politics came centre stage as British politicians tried to deal with Irish nationalism and calls for Irish independence, or what they described as “the Irish Question”.

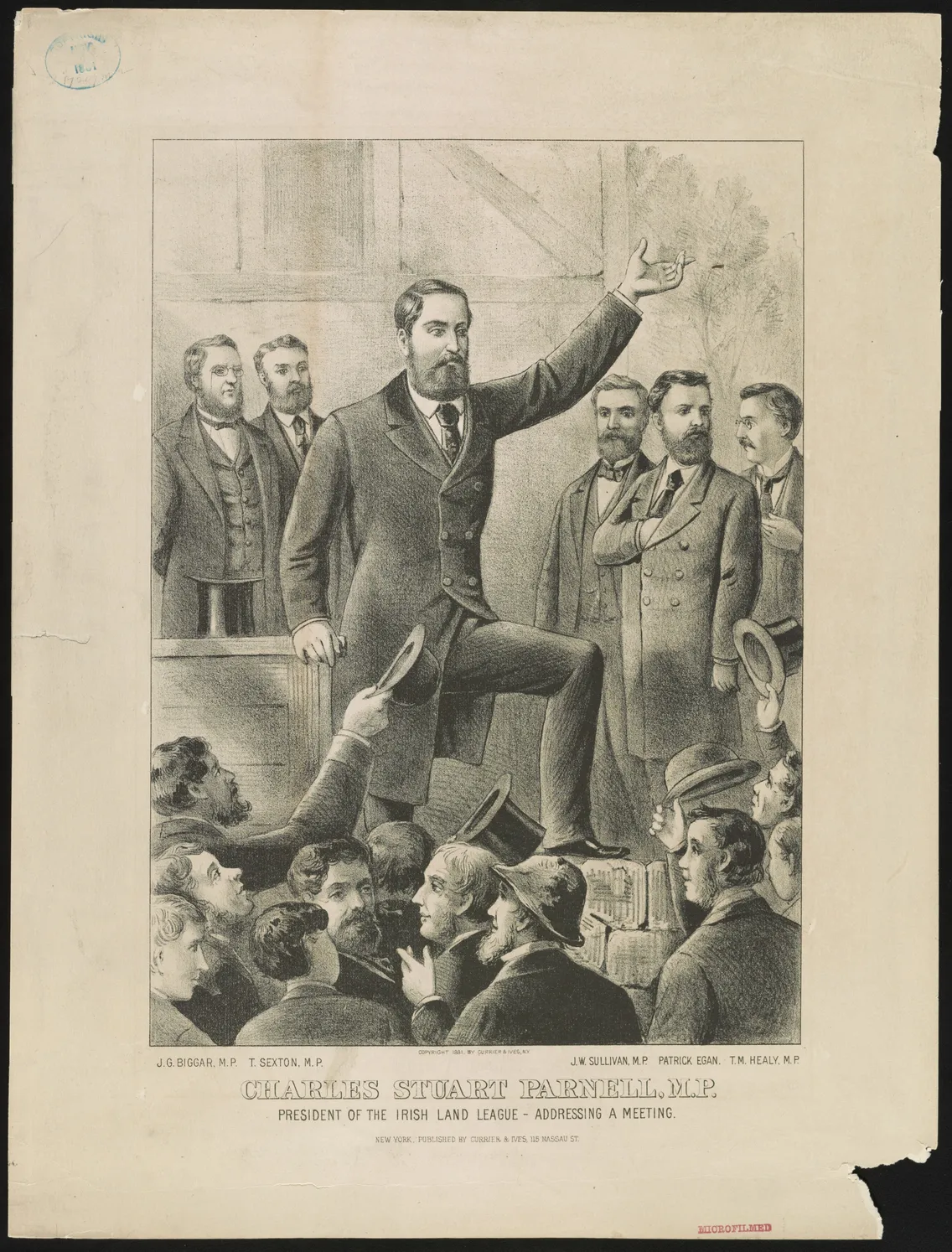

A charismatic politician called Charles Stewart Parnell led the Irish party. Parnell was a Protestant landowner who supported the cause of Irish political self-determination. Ireland previously had a Parliament of its own, but it was abolished in 1801. Irish members of Parliament sat in the House of Commons alongside MPs from Scotland and England all through the 19th century.

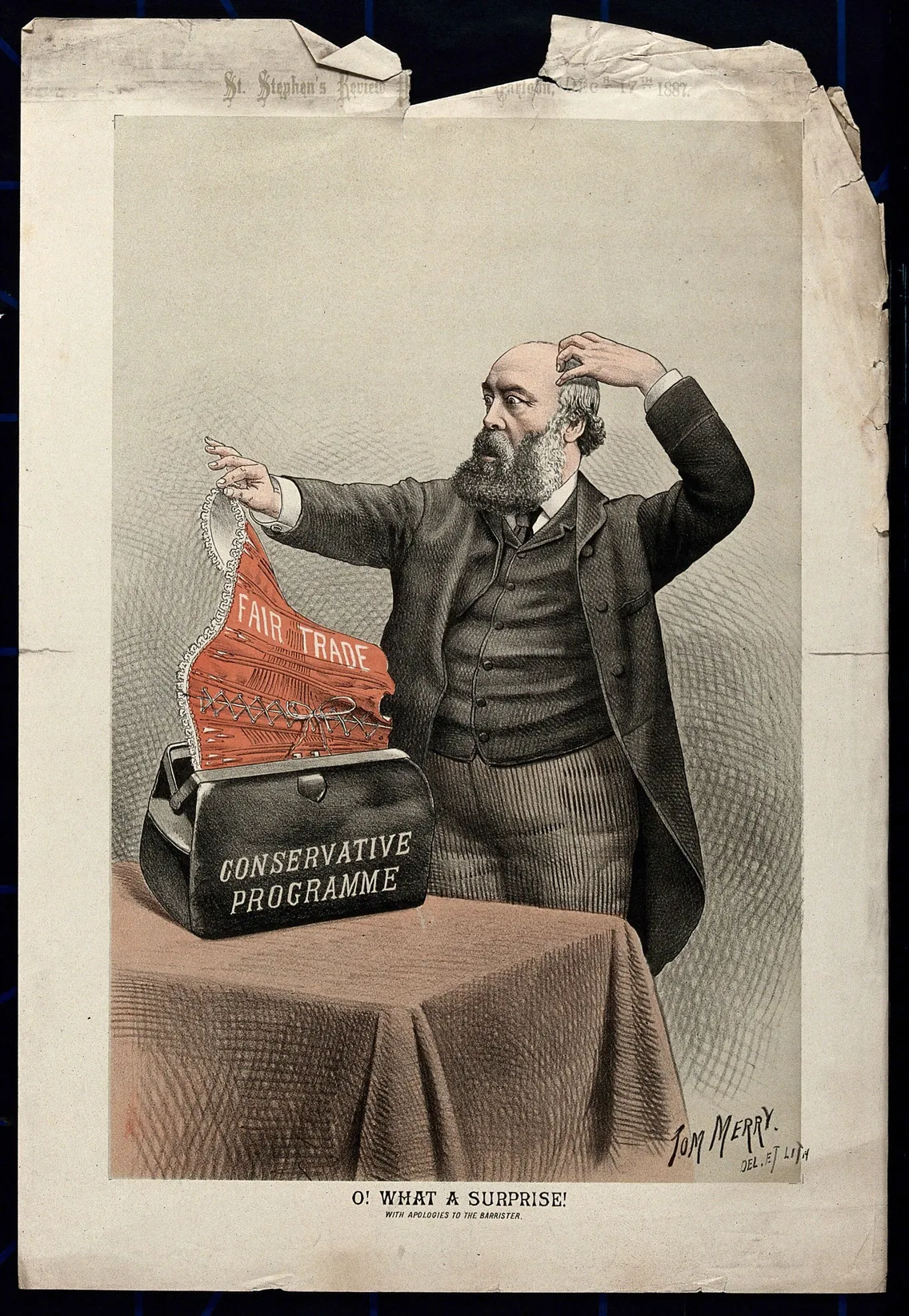

In 1885, Lord Salisbury led the Conservative government. One of the big political questions of the day was the so-called “Eastern Question” (which is also commemorated in an 1878 handkerchief in the museum’s collection) and a war between Serbia and Bulgaria.

Cotton handkerchief titled ‘The Eastern Question’ (1878). When folded correctly, the portraits of Prince Gortschakoff, Count Andrassy, Suavi Pacha and Prince Bismarck reveal a portrait of Benjamin Disraeli.

Russia’s expansion into territory owned by the Ottoman Empire was a constant topic of political discussion in late Victorian London. The so-called “Irish Question” – which referred to finding a solution to Ireland’s political concerns – was rarely the focus of the government’s attention.

Impact of the 1884 Third Reform Act on British politics

Meanwhile, the political environment in which Parliament operated was changing significantly. Following the passing of the 1884 Third Reform Act (which extended voting rights to men in the countryside) led by Gladstone, there was a significant addition to the size of the voting population of the United Kingdom. About 5 million men over 21 years of age were now entitled to vote. A large number of the new voters came from the labouring classes.

By the mid-1880s, Gladstone had been in politics for 40 years and had served as Prime Minister three times. By then, he had converted to the concept of Irish Home Rule. However, he did not make this view known publicly. His view was that it was more likely that Home Rule would be granted if he were able to arrange a joint approach with the Conservatives, as they held control of the House of Lords and they could block any bills they didn’t support.

Following the elections of 1885, the Irish Parliamentary Party was the most popular party in Ireland, having won 85 out of 105 Irish seats. They now held the balance of power in the new Parliament.

The secret meeting between Gladstone and Balfour

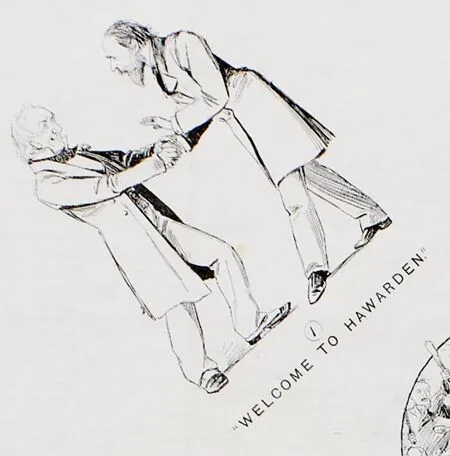

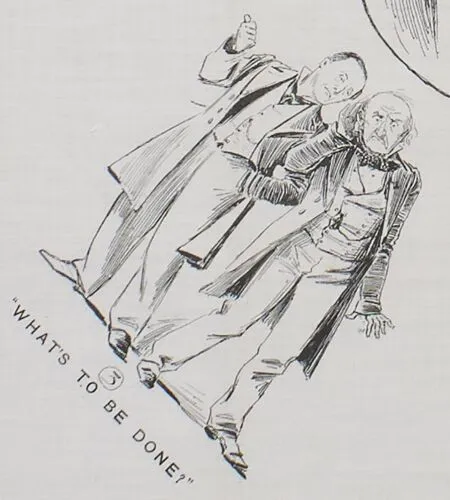

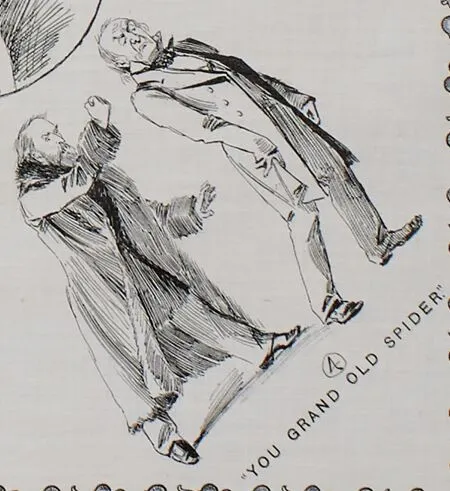

Linen handkerchief with a lithographic print in black ink, 1886. This handkerchief appears to commemorate a meeting between Balfour and Gladstone to discuss the Irish Question.

The story told by the handkerchief relates to a meeting between Gladstone and Arthur Balfour, a nephew of the Conservative leader, Lord Salisbury. On 15 December 1885, Gladstone met with Balfour and told him that if the Conservatives decided to support Home Rule, he would offer them his support.

For this strategy was to work it was important that secrecy be maintained. Many members of Gladstone’s Liberal party were not supportive of Home Rule and large numbers of the newly enfranchised voters were strongly imperialistic and unlikely to be in favour of Home Rule either.

The Hawarden Kite incident and its aftermath

Unfortunately, for Gladstone, at the same time as his meeting with Balfour, his own son Herbert leaked a story to the press suggesting that his father was a supporter of Home Rule for Ireland. This incident became known as the Hawarden kite, suggesting that Herbert was testing out possible public reaction to this change of policy (Hawarden refers to the name of Gladstone’s home). There has been much debate since around the motives for Herbert’s intervention but the consensus appears to be that it wasn’t sanctioned by Gladstone and was simply a mistimed intervention.

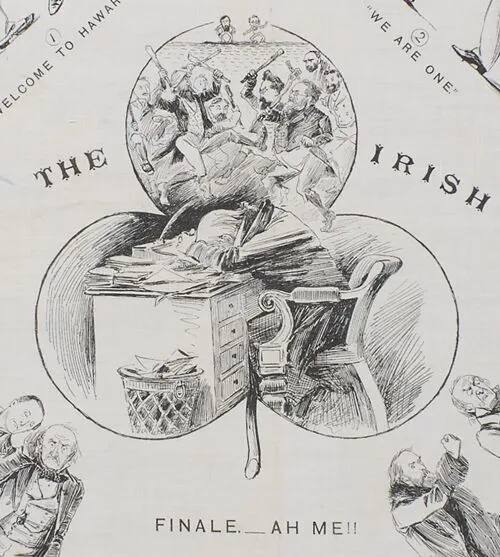

At the centre – encased in a shamrock – we see a depiction of the political chaos that followed the Hawarden Kite incident.

The result was a major political rift, some of Gladstone’s key supporters abandoned him, Parnell allied his party with Gladstone and the chances of a joint Tory/Liberal approach to the “Irish Question” was lost. Gladstone subsequently introduced a Home Rule for Ireland bill in 1886, but it was defeated by 30 votes. A Home Rule Bill was finally passed 26 years later in 1912, but by then Irish politics had changed irrevocably. Parnell and Gladstone were both dead and in the decade running up to the First World War a new generation of young people abandoned constitutional politics to adopt a more radical path.

The handkerchief is testament to both the importance of the politics of Irish Home Rule in the late 1880s (which is when it was printed), as well as a nod to the reigning fashion of ‘topical’ mouchoirs. Whether these were printed en masse, or just a select few as a lark (maybe commissioned by the Conservative Party), we don’t quite know. The border of entwined shamrocks suggest it was printed with a specific audience in mind, unlike those that were imported with generic borders, and the centres filled in in London, or later Lancashire. This particular handkerchief made its way to the London Collection as part of the ‘Balfour papers’.

Finbarr Whooley is Director of Content at London Museum.