27 March 2018 — By Caitlin Davies

From prison to parliament: Suffragettes & Holloway

Holloway prison was, in the early 1900s, the largest women’s prison in Europe. Author Caitlin Davies delves into its history, and the extraordinary stories of the Suffragettes imprisoned there.

Holloway prison was, at the time of the fight for female suffrage, the largest women’s prison in Europe. Hundreds of Suffragettes were incarcerated there, many suffering hunger strikes as they continued their campaigning from within the prison walls. Caitlin Davies’ book Bad Girls: a History of Rebels and Renegades (2018) delves into the history of Holloway, shedding new light on the extraordinary stories of the women imprisoned there, including the Suffragettes.

Here she talks about how she researched Holloway prison and the fascinating histories of the Suffragettes featured in her book.

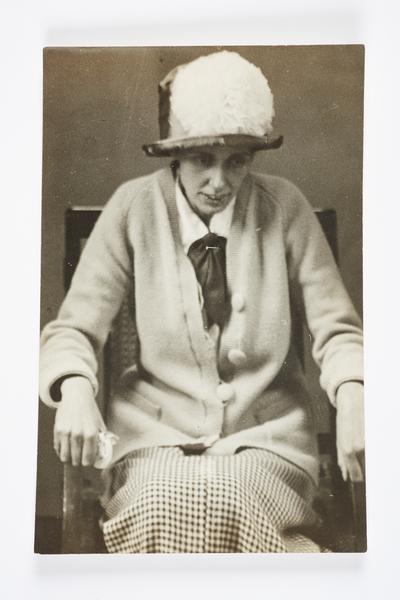

Caitlin Davies, author of 'Bad Girls: A History of Rebels and Renegades'.

When did you first become interested in Holloway prison?

I grew up a short distance away, and like anyone who grew up in Islington in the 1960s I remember it as a kind of medieval castle. I was about seven years old when they started knocking it down for redevelopment, and I remember thinking: who are the women in there, what have they done? When I was training to be a teacher in the late 1980s, I chose to do a work placement in the new Holloway prison, because I was scared of imprisonment, and I wanted to see what it was like inside.

I was in there for six weeks, teaching creative writing in the education centre. I learnt a lot, about the prison, and why women were there: many had been coerced into bringing drugs into the country, for example.

Later, while working as a journalist in Botswana I was arrested and put on trial twice, each time facing a two-year sentence. The charges were dropped in the first case, and in the second I was acquitted, but my source was imprisoned.

When I heard that Holloway was closing down a few years ago, I thought this is my last chance to write its full history. So I went in to research the prison, and interview the governor, chaplain, wardens and the last prisoner to be released. The officers gave her a sort of parade when she came out, holding up their batons.

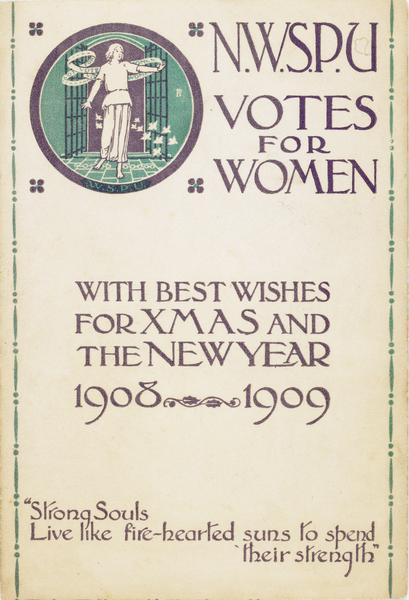

The painted banner depicts two policemen guarding the entrance to Holloway prison, out of which a suffragette prisoner can be seen waving a banner with the slogan 'Votes for Women'.

How did that personal connection change the way you wrote about Holloway?

What I wanted to do with Bad Girls was not to write a dry history, but to tell the stories of the women who were there, both the inmates and the staff. So I went on the hunt to find women who had been imprisoned or worked there. I found relatives of the Duchess of Sutherland, who was jailed in 1890.

She was married to one of the richest men in the western world, and after he died there was a family argument over a will. She had burnt an important document and was charged with contempt of court for refusing to reveal its contents. Sending a duchess to the biggest women’s prison, where she’ll be alongside women charged with vagrancy or prostitution: it was intended to take her down a peg or two.

She was sent to Holloway as, essentially, a lesson: Holloway was used to make women know their place in one way or another.

Suffragettes at Holloway prison

Was that also why the Suffragettes were sent to Holloway prison?

The first Suffragette arrived at Holloway in 1906. To begin with, the Suffragettes were bound over to keep the peace, asked to promise not to re-offend, and given a fine. When they refused to pay the fine, they were sent to Holloway. As they escalated from minor acts of street protest to criminal damage, they received more severe sentences.

In the same way, they escalated their resistance to Holloway’s prison rules. As more Suffragettes were imprisoned, they fought with prison authorities more and more.

When the leading lights of the suffrage campaign arrived at Holloway they would be put in the prison hospital, to keep them away from the hundreds of other Suffragettes already imprisoned. Behaviour would spread between prisoners, so if one smashed a window to improve the ventilation, the others would as well. The governor had a breakdown and left. He found the Suffragettes a thorn in his side and thought the press helped to encourage them.

Did the Suffragettes seek publicity from their imprisonment?

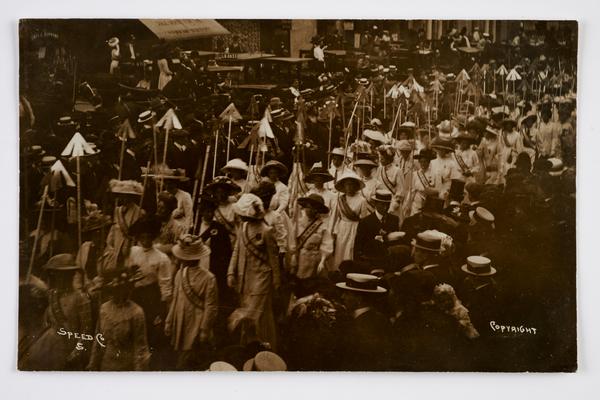

This was the time when the British public first learnt what was going on inside Holloway prison. You had up to 200 Suffragettes being admitted on a single day. These were often educated women, some with influential friends. They were clearly documenting what was going on, they hoarded their arrest warrants, smuggled out letters, kept secret diaries. When they were released they would be greeted with cheering crowds and given a medal, the Holloway brooch. Sometimes they would give interviews to journalists on the day of their release. They didn’t just promote the cause of suffrage, but also wanted to make things better for the women imprisoned in Holloway.

Holloway was based on the separate and silent system: you were isolated in your cell and no-one was supposed to talk to each other. The Suffragettes started defying prison discipline and making constant complaints and demands. At first the suffragettes looked at penal reform as distracting from their core purpose of getting the vote. Then these campaigning women would go to the prison chapel and see 16-year-old girls and ask, “why are they here?”

“Holloway was based on the separate and silent system: you were isolated in your cell and no-one was supposed to talk to each other”

Did they succeed in making things better?

They had a variety of different goals – one was to change how Suffragettes were treated. Holloway had different divisions of prisoners, a kind of class system. First division prisoners could order in their own food and wine, and have someone clean their cell. They could have visitors and letters. To begin with suffragettes were not put in that class.

In theory, it was the crime that determined an inmate’s division. If you were found guilty of libel or were from a privileged class you would be put in first division. The big thing for the Suffragettes was they wanted to be recognised as political prisoners, so that was why they went on hunger strike. This was another way they were fighting the system. The hunger strike was, ‘if we’re not going to be treated as first-class prisoners then we will refuse to obey the rules and we will refuse to eat’.

As well as the resistance, they would sometimes have fun in the prison: the Suffragettes organised a mock election, played games, produced a magazine. There’s a wonderful scrapbook recording all this that was kept by a woman named Olive Wharry. She was actually declared insane by the prison medical officer – she had burned down Kew Gardens tea pavilion and was on hunger strike for about five weeks. It was easier to pathologise female defiance than engage with it politically. It was very handy to say that the Suffragettes were insane.

Holloway as the graduating university for militancy

How else did the prison authorities deal with the Suffragettes?

Something I really wanted to find out was how the Suffragettes related to the female prison wardresses. I was fascinated to read the diary of Alice Hawkins, a working-class Suffragette, who worked as a machinist. She really identified with the non-suffragette prisoners and also with the prison staff.

There was definitely a close relationship. A lot of Suffragettes wrote about wardresses who comforted them, who held them while they sobbed. But at the same time these female staff were holding them down while they were force-fed.

That sounds brutal, how did the Suffragettes cope with that?

There was a support network. They rented a house on Dalmeny Avenue near the prison, where they housed Suffragettes who had just left Holloway. They also used this as a headquarters and would serenade the prisoners from the roof of this house. When the Suffragettes finally bombed the prison, in 1913, they did it from that house’s garden.

What do you think has been the legacy of the Suffragette movement?

They have been an extraordinary inspiration. Here is a large group of women who were refusing to obey the rules. And as the years go by you see parallels with other groups – the initial Women of Greenham Common March used the Suffragette colours of white, green and purple. They were very aware of those connections, not least because many of them were imprisoned in Holloway themselves.

In 2017, the feminist direct action group Sisters Uncut occupied the Holloway visitors’ centre. They used the words of the Suffragettes on their banners: deeds not words. They set off smoke bombs in the colours of the Suffragettes. When I heard that I said, well, that’s the last chapter of my book sorted!

“The struggle of the suffrage movement…should be taught properly about at school”

Why do you think it’s important to remember the fight for women’s suffrage?

The obvious thing is that the struggle is far from over. If you look at prisons and the reason that women are in prison now, those haven’t changed from the days of the Suffragettes – sexual violence, domestic abuse, drug and alcohol abuse.

I think that the struggle of the suffrage movement is something that children should be taught properly about at school. Children today learn about things like the Cat and Mouse Act, but I think they learn a story of victimisation rather than story of bravery. Someone described Holloway as the graduating university for militancy. They organised and we need to remember that. We need to know the real story of the Suffragettes.