05 August 2020 — By Georgina Barrett

From mammoths to pets: London's prehistoric beasts

Woolly mammoths, elephants, hippos and cave lions once roamed the fields and hills of London now populated with modern skyscrapers, bustling industry, and 9 million of us humans.

Fragments of animal bone found on an archaeological excavation at Custom House on Lower Thames Street near the Tower of London.

Our capital is an ever-evolving metropolis, steeped in history and dating back millennia. Prehistoric London was a sparsely populated landscape that would be unrecognisable to most present-day Londoners. Over time, the lives of London’s prehistoric human inhabitants transformed as new technologies and ways of life developed, and so did the animal inhabitants who lived alongside them.

Follow us on a journey of London animals from the Old Stone Age to the Iron Age.

Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age), before 8,500 BCE

The earliest evidence for human activity in the London area comes from the Palaeolithic period, an era which lasted hundreds of thousands of years. In this period massive primeval beasts, known as ‘megafauna’, ruled the roost while early humans and our evolutionary cousins Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis (or ‘Neanderthals’) roamed the landscape.

“Most of our evidence of ancient Palaeolithic beasts comes from excavations at sites like Trafalgar Square and Pall Mall”

London was home not only to the famous woolly mammoths of the ice age but also to straight-tusked elephants, giant oxen (known as aurochs), and even hippos and cave lions. Most of our evidence of these ancient beasts comes from bones excavated from sites across the London basin, including sites at now central locations such as Trafalgar Square and Pall Mall.

Rhino humerus recovered from the River Thames between Canvey Island and the Chatham Light between Tilbury and Southend, Essex.

This part of a woolly rhinoceros humerus (thigh bone) was found near Canvey Island on the Thames estuary. Life during this period involved constant travel in small family groups, and hunting or scavenging these megafauna and smaller mammals for food, fur, and bones. The distal end of this thigh bone has been smashed in an unusual way, possibly by an early human or close relative to get at the nutritious bone marrow inside.

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), 8,500–4,000 BCE

As time passed, woodland began to replace the open plains where ice age megafauna had thrived. Smaller mammals like deer, wild horses and boar became more common, while the larger beasts of the Palaeolithic eventually died out. These changes forced Mesolithic Londoners to adapt to new ways of life.

In the Mesolithic, prehistoric communities stopped roaming constantly and started to settle in one place for seasons at a time, shaping the environment around them as they did so. They burned and chopped down forests for raw materials and to make it easier to hunt their prey. We can tell from isotope analysis of human remains that meat was important to the Mesolithic diet – although fish and seafood would also have been eaten by people living near the coast and along the Thames.

“Animals were not only hunted for their meat, but also for their bones and antlers which were useful for making tools”

An antler beam mattock found in 2004 on the Thames foreshore at Surrey. It has an oval perforation where a wooden handle would have been attached, which has not survived.

This mattock made of deer antler would have been used for digging and cutting the earth, and was found on the Thames foreshore in 2004. While bones were already used for tools in the Palaeolithic, we see an explosion of such tools in the archaeological record from the Mesolithic, showing just how resourceful prehistoric communities were becoming.

Neolithic (New Stone Age), 4,000–2,200 BCE

Often considered one of the most important periods in human history, the ‘Neolithic revolution’ saw fundamental life changes for the people of London and the prehistoric world. The domestication of plants and animals and introduction of pottery – new innovations from the Middle East – prompted communities to settle more permanently in the landscape and take up farming. Agriculture and pastoralism gradually replaced hunting and gathering as a way of life.

“We begin to see more evidence for domestic cattle, sheep and pigs at Neolithic sites”

Wild animals like deer, boar and foxes continued to live in the grass and woodlands between settlements, but we begin to see more and more evidence for domestic cattle, sheep and pigs at Neolithic sites. Cattle provided meat as well as milk which supplemented the Neolithic diet.

A sherd of pottery discovered by MOLA at a site in Shoreditch in 2020. It features an unusual decoration, and is part of the largest group of Early Neolithic pottery ever found in London.

This pottery sherd, found by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) at a site in Shoreditch, has been tested to reveal traces of dairy products. It also features an unusual decorative pattern made by pressing deer hooves into the clay when wet. This shows how Neolithic communities made use of both tame and wild animals.

Bronze Age, 2,200–700 BCE

By the Bronze Age, early Londoners had begun to perfect agricultural techniques, and the farming of animals intensified on a large scale. Droveways designed to herd flocks of sheep and cattle became common, and demonstrate how abundant domestic livestock were in Bronze Age London.

Farming was becoming ever more popular, but people did not stop hunting for their food. Wild boar, deer and water fowl like ducks were common prey. Hunters would have used bows and flint arrows, like these from Holloway Lane in Hillingdon, to hunt their prey. Bronze-working technology had been introduced, but since bronze was rare and costly, flint, bone, and antler tools were still commonly used.

These flint barbed and tanged arrowheads were found in a pit at Holloway Lane alongside the remains of a dismembered ox or auroch.

Cattle and tame horses were used as beasts of burden as well as for food. Cattle had the strength and endurance to plough fields quicker than any human, while horses were ridden for warfare and hunting. Native wild horses had gone extinct in the Mesolithic, but were reintroduced from Eurasia and as high-status animals owned only by the most powerful people in Bronze Age society.

“A number of high-profile Iron Age coin hoards have been discovered in the London area”

Iron Age, 700 BCE – 43 CE

In the Iron Age, the people of what would become London began to feel the influence of classical civilisation from the European mainland. Coins were first traded with, and subsequently adopted and copied by, society’s elites before becoming common in Britain. A number of high-profile Iron Age coin hoards have been discovered in the London area, including at Uphall Camp in Ilford (one of the largest hill forts ever discovered). The finds at Uphill Camp were especially rich in ‘potin’ coins that typically feature stylised designs of animals.

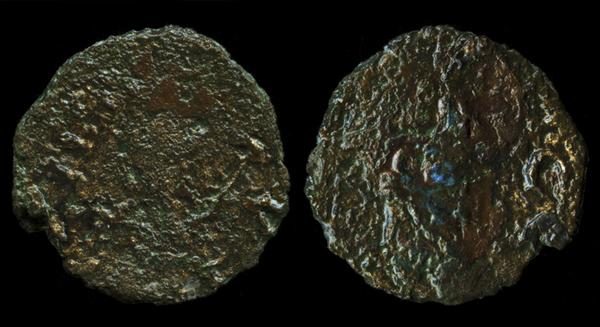

A selection of Iron Age coins showing the varied ways horses were depicted on prehistoric coinage. Some are more obvious copies of earlier Roman coins from Europe.

These coins from Ilford are decorated with horse figures testifying to the status of horses as highly prized and valuable creatures. They were increasingly used to pull carts and chariots, other important technologies arriving from Europe. Wheeled vehicles pulled by animals made trade and travel much easier and opened up a world beyond their farms and villages to Iron Age Londoners for the first time.

Prehistoric remains recovered from London during archaeological excavations enable us to piece together the story of the human past through our predecessors’ relationships with the animals of London. From megafauna to loyal companion, animals have shaped the landscape and the lives of Londoners from prehistory to the present, and continue to influence how we live in our city to this day.

Georgina Barrett is Archaeological Collections Manager at London Museum.