20 February 2023 — By Beverley Cook, Colin Knight

From avoiding the gallows, to leading a mutiny

In 18th and 19th centuries, many convicts of the British empire faced a grim choice: execution or exile. Captain William Swallow's extraordinary journey from penal colony to freedom stands out among thousands sent to distant shores like Tasmania.

Newgate prison: A place of despair and desperation

For hundreds of years the notorious Newgate prison was feared by Londoners as a place of despair and desperation. Here, men, women and minors condemned to a public execution spent their last days, frantically urging friends and family to petition the monarch for a reprieve from death. During this anxious wait, many prisoners wrote last letters and engraved tokens to loved ones, while others turned to religion, drink or even took their own lives to avoid the gallows and an uncertain fate.

By the 1820s, however, the conditions and atmosphere within Newgate had changed dramatically as the majority of those condemned to death were spared a public execution. During a visit to the prison in the 1830s, Charles Dickens observed 25 condemned prisoners in the day room, who, anticipating a reprieve, showed “very little anxiety or mental suffering”.

From execution to transportation

One of the key reasons for the increase in reprieves was Britain’s expanding empire that provided an alternative harsh punishment to execution. From 1718, the transportation of convicts to America supplied the plantations with some of the labour required to exploit the riches of the land.

Although the American War of Independence temporarily halted transportation from 1776, a new opportunity soon arose with the colonisation of land in Australia and Tasmania. The need for cheap labour in this “vast new land of opportunity” ultimately became more important to the British state than the public execution of its citizens.

“Many spent months in these floating prisons moored along the River Thames – made famous by Dickens”

Britain’s first penal colony in Australia was established in Botany Bay, New South Wales, in 1788 with the arrival of 548 male and 188 female convicts. Those reprieved from execution were removed from Newgate and sent to prison hulks (decommissioned warships) awaiting their long passage to the penal colonies. Many spent months in these floating prisons moored along the River Thames – made famous by Dickens with the character of Abel Magwitch in Great Expectations.

The appalling verminous conditions resulted in many inmates succumbing to “gaol fever”, cholera and typhoid before they could depart on the long voyage.

A remarkable document in the museum’s collection provides an insight into the penal system at this time. The ‘Statement of Prisoners held in Newgate in 1830’ identifies that 1,200 convicted prisoners were removed from the prison to the hulks that year. It is likely this included the 986 prisoners awaiting transportation, 673 of whom received the minimum sentence of seven years. In contrast, only six were publicly executed outside Newgate that year.

Convict tokens and their stories

Convicts awaiting transportation often presented loved ones with smoothed coins engraved with messages of affection by fellow prisoners skilled in metalwork for a fee. Known as ‘leaden hearts’, the tokens could be highly decorative but in reality represented the fear of never returning home from distant, unfamiliar lands.

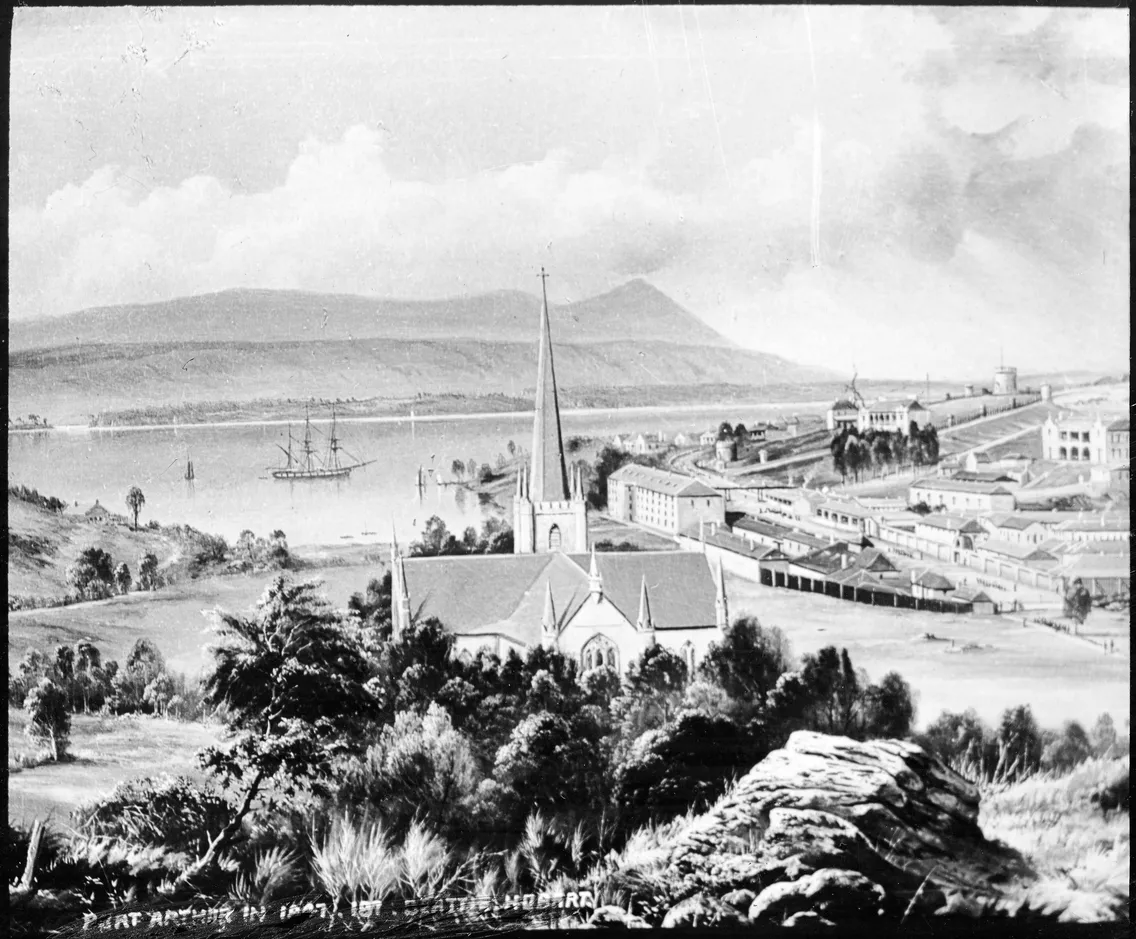

The Port Arthur penal settlement

From 1803, until the end of transportation in 1853, Van Diemen’s Land – now known as Tasmania – was the main penal colony in Australia. About 75,000 convicts were sent there, accounting for approximately 40% of all convicts sent by the British to Australia. One in five were female convicts. A number of children were also transported with their parents. Few returned home.

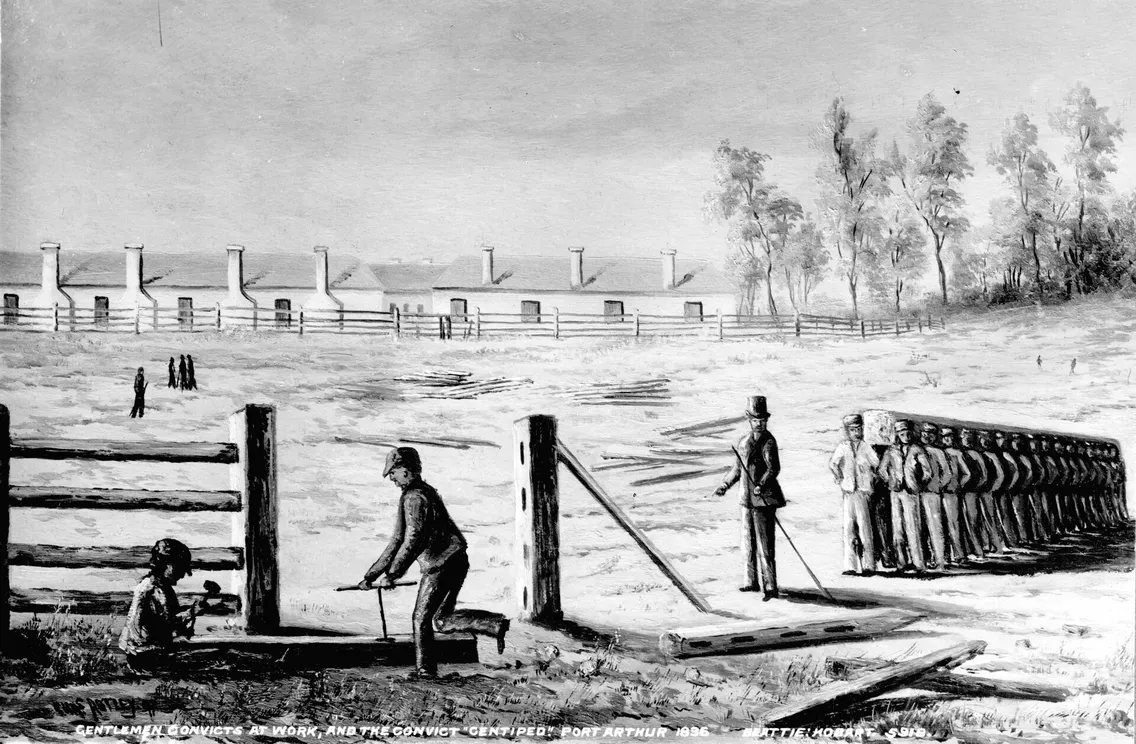

After arrival, a considerable number of convicts reoffended and were then sent to the feared Port Arthur settlement, which took on the mantle of Secondary Punishment in 1833. Here they were taught new skills, including shipbuilding. Of all the laborious occupations convicts were forced to carry out during their time there, timber-getting was the most punishing, yet also the most profitable.

“Transportation sentences ranged from seven years to life”

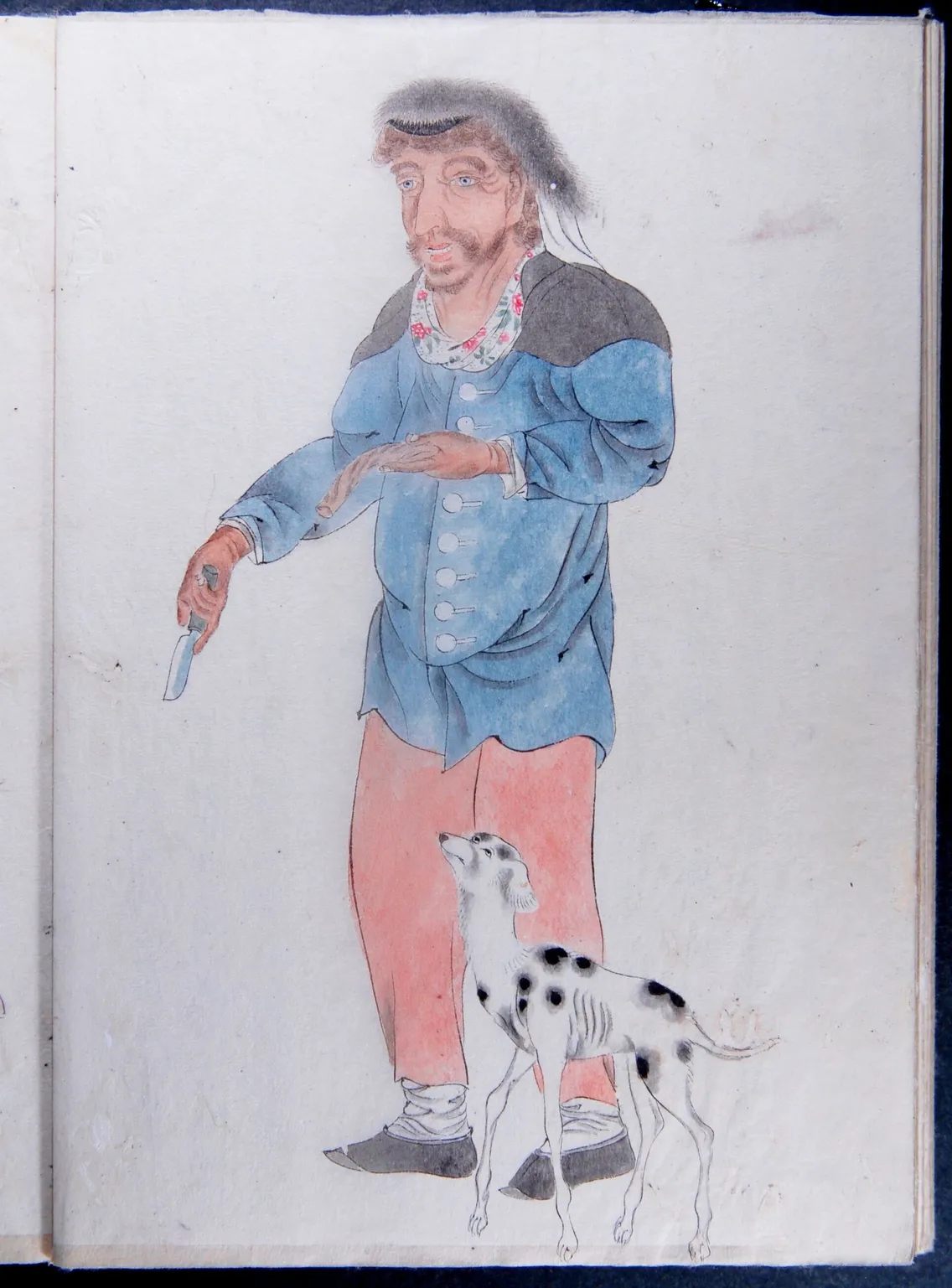

Transportation sentences ranged from seven years to life. Those who managed to escape before their sentences risked execution if caught, as “returning to Britain from transportation” remained a capital offence. While many served their sentences compliantly, earning their “ticket of leave” or parole often before the end of their sentence, others remained non-compliant, attempted to escape or returned to their criminal ways. One such colourful character who is linked to both the history of London and Port Arthur is William Walker, who also used the aliases Swallow and Brown.

William Walker, alias Swallow, alias Brown

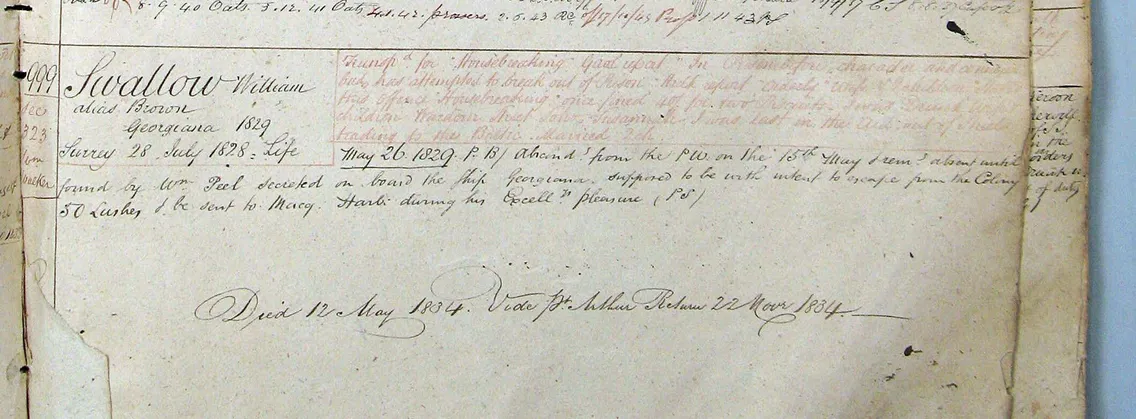

William Walker was formerly a mariner from County Durham. Convicted at the Durham Quarter Session on 8 January 1821 for stealing a quilt, he was sentenced to transportation for seven years. Leaving behind a wife and three children, William – described as “5’8 3/4” tall, brown hair, blue eyes with a small scar on his nose and chin” – arrived at the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land aboard the Malabar in 1821. He soon absconded and returned to England where, on arrival, he adopted several aliases.

Turning again to crime, William was convicted for tier-ranging, plundering ships at night in the river, and eventually tried at Guildford Assizes on 28 September 1828 for sheep-stealing. His sentence was transportation for life and he returned to Van Diemen’s Land in 1829. On arrival, he attempted to hide in the transportation ship, Georgiana, but was discovered and ordered to be sent to Macquarie Harbour, a secondary punishment station located on the remote west coast.

“Appointed captain by the mutineers, Swallow later appealed he was forced to take part”

The Cyprus Mutiny

Travelling with Walker to Macquarie Harbour aboard the brig Cyprus were 62 people, including the wives and children of some of the station personnel, ships crew and 31 convicts. While anchored in Recherche Bay, some of the convicts – who had been allowed on deck, as the Captain went fishing – took over the vessel and set sail, leaving behind the officers and families and any who did not want to join them. The 17 mutineers appointed William Swallow as sailing master and the brig proceeded on an epic voyage that took in New Zealand, Chatham Islands, Tonga, Japan and finally Canton, China where the seven remaining convicts, including Swallow, scuttled the ship and claimed to be shipwrecked mariners.

In 2017, a Japan-based English history buff Nick Russell found two samurai accounts by Makita Hamaguchi and Hirota at the Tokushima Prefectural Archive, and joined the dots to find that they described the Cyprus and Swallow’s arrival in Japan in 1830.

In China, the men were questioned by the local English officials. They were returned to England along with other prisoners and committed for trial at the Admiralty sessions. Two of the mutineers – George James Davis and William Watts – were hanged at Execution dock, in Wapping, London in December 1830 and became the last men to be hanged for piracy in Britain.

But what of Swallow?

Remarkably Swallow again evaded the gallows claiming he had been forced to take part in the mutiny as the only experienced sailor aboard the Cyprus navigating 14,000 miles of ocean against his will. Surprisingly, his story was corroborated by a fellow convict, Popjoy, who had refused to join the mutiny and remained at Recherche Bay. For his efforts in saving those abandoned on shore in the wilderness, Popjoy had been granted a pardon and subsequently became a respected seaman in service with the East India Company.

The story of Swallow being forced to take part in the mutiny was believed by the Admiralty court. However, Swallow was again sentenced to transportation on a charge of “returning from transportation”. He arrived in New South Wales in July 1831, but with no further opportunity to abscond, was within months transferred to Port Arthur, where he died of consumption in 1834, aged 42. He is buried in an anonymous grave upon the Isle of the Dead – Port Arthur’s tiny island cemetery.

Curator of Social and Working History at London Museum, Beverley Cook, was the lead curator of our exhibition, ‘Executions’, which ran at London Museum Docklands until 16 April 2023. Colin Knight has been with the Port Arthur Historic Site for over 30 years. Working in the guiding team, he is also the voice visitors hear on The Port Arthur Experience podcast.