25 July 2022 — By Rebecca Redfern

Following the Roman princess of Spitalfields

Senior Curator Dr Rebecca Redfern first became interested in the intriguing Spitalfields Princess as she was excavated in 1999. Since then, as a student recording the excavation on VHS to now being responsible for her care, this is a fascinating and endearing story that spans two decades.

A woman depicted as a Roman laureate female, possibly a Muse, on one of a pair of miniature bracelet plaques made of gold.

Excavation at Spitalfields Market

When talking about the city’s history, there is one ancient Londoner who deserves much celebration! She has gone by many names – the Spitalfields Princess, Spitalfields Lady, among others – but sadly, we don’t know hers. It is, however, very likely that her burial place would have been marked by a tombstone, giving her name, origin and age.

Her burial was discovered during excavations at Spitalfields Market near Liverpool Street Station in 1999, and was covered extensively by the media at the time, including in a special episode (The Princess and the Pauper Part 2: Princess of the City) of the BBC show Meet the Ancestors. The burial is unique in London, and the journey of the newly discovered stone sarcophagus from the dig to the museum for excavation and analysis was captured by the TV programme.

I can remember watching it as an archaeology undergraduate, recording the episode on a VHS tape to watch again. I thought it was absolutely incredible how all the different experts and specialists worked together to ensure that the large sarcophagus reached the museum safely and was carefully excavated so that all of the evidence could be recorded.

Very quickly afterwards, London Museum put the artefacts and remains of the Spitalfields Princess on display, allowing the public to see the amazing sarcophagus, lead coffin and the incredible grave-goods. Around 10,000 people queued to visit this ancient Londoner and see the precious artefacts that had remained hidden for nearly 2,000 years.

How the Spitalfields Princess influenced my academic pursuits

I was very glad that I had recorded that episode, because even though the site report had not been published, a question about her burial was in my final exams. The episode also influenced my choice of Master’s thesis, as I decided to look at the health in Roman urban centres. I was able to visit the Museum of London's Archaeological Archive (MoLA) and the Archaeological Archive to collect data, and see for myself all the outstanding finds from the Roman city on display in the museum’s gallery.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to see the finds from her burial, as they were being recorded and studied, but I did get to meet Bill, the osteologist who first studied the remains of the Spitalfields Princess.

The Spitalfields Princess’ lead coffin, with the lid decorated with scallop shells.

Understanding the burial context

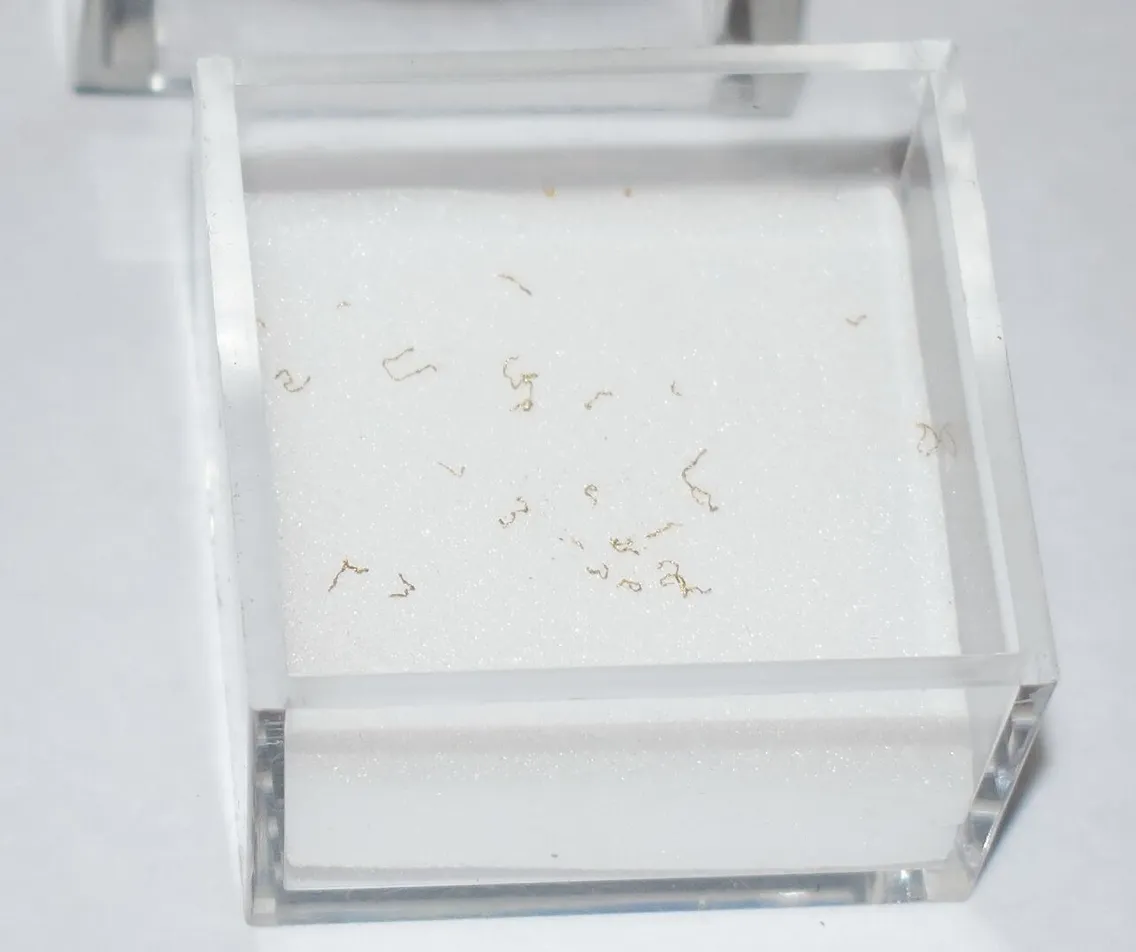

I went on to study for PhD – more Romans. And all through that time, more information was being shared about the Spitalfields Princess – that she had grown-up outside of Britain, perhaps her family had come from the Basque region of Spain, and that her grave-goods were of exceptional richness and quality. As she had been laid within a lead coffin, which was then placed within a stone sarcophagus, meant that fragments of gold and silk fabric she had been wearing and the bay leaves under her head had survived. This is so rare and wonderful – to be able to see a bay leaf that may have been from a tree in London and picked so many years ago, still astonishes me!

“Analysis of the grave goods showed that the beautiful glasswork had been made in Europe”

Towards the end of my PhD, I saw an advert for an osteologist to work as part of a team recording the human remains excavated from Spitalfields Market. At the interview, I remember speaking about how inspirational the excavation and research had been to me, and how incredible it would be if I could join the team. I was lucky enough to join the team… but never got to record any Romans.

That work was done by Bill and Natasha, but they did let me look at her skeleton, and because our office was near all the other specialists, my colleagues who were looking at the environmental remains and the finds, always let me know when they were studying those grave-goods, so I could visit and hear what they’d found out.

Insights into the Princess' origins

At the end of my time with the Museum of London Archaeology, my colleagues had established that the Spitalfields Princess had died in her early 20s, but there was no evidence for how she may have died. Analysis of the grave-goods showed that the beautiful glasswork had been made in Europe, she had been buried wearing a tunic of damask silk with purple wool and gold thread tapestry decoration, the glassware and objects made from jet were used for personal ornamentation and for perfume/aromatic oils.

The lid of the stone and jet canister was marked on the inside with an “x”, and the bay leaves had most likely been covered with fabric to make a pillow. The burial remained on display, accompanied by a reconstruction bust of the Spitalfields Princess.

Years of research suggested that her burial was so expensive and contained rare and luxury objects because, for the people who loved her, she had died too soon and so her burial reflected the dowry she would have had at marriage.

Can you spot the 'X'? The lid of the stone and jet canister was marked on the inside with an “x”, but we don’t know what it stands for.

Ongoing research and discoveries

In 2008, I became Curator of Human Osteology at London Museum, meaning that I was responsible for caring and researching the museum’s human remains, over 20,000 individuals, but of course, the one person I was most interested in was the Spitalfields Princess. Since then, I have been fortunate enough to work with colleagues at universities across Britain and Europe to explore her burial further. We have established that her body had been treated (embalmed) with costly resins originating in the Mediterranean, that she grew-up in Italy and had light brown hair; we are waiting for more results about her genetic heritage to be shared with us.

In 2020, the site report on the Roman excavations at Spitalfields Market was published, but we still don’t know what the “x” on the lid stands for.

I am not the only one to have been inspired by the Spitalfields Princess. In 2001, the 2019 Booker Award winner Bernardine Evaristo published The Emperor’s Babe, which imagines the Princess’ life and death in Roman London, through the character of Zuleika, a pulcherrima babe – a book which led me down other research paths such as the Harper Road woman (so called because her skeleton was excavated from Harper Road) and ancient DNA.

Rebecca Redfern is Senior Curator (Archaeology) at London Museum.