25 September 2022 — By Paul Bridges

Executions & death-penalty reforms in Britain

In Britain, there’s been a demand for reforms and, later, abolishment of death penalty since the 18th century. Global organisations like Amnesty International continue the legacy of earlier reformers by campaigning against capital punishment.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Death penalty history, reforms and abolition

The death penalty has been in existence around the world for thousands of years. Legal accounts from pre-Christian times prescribing the use of the death penalty have been found in China, Babylon, Egypt, Greece and Rome and for a huge range of crimes and methods of execution were often unspeakably cruel, including crucifixion and burial alive.

In Britain, by the 10th century, the most frequent method was hanging, although William the Conqueror banned all executions except in times of war. Nevertheless, the death penalty increased in frequency and was applied to ever more crimes throughout the mediaeval period and into the Tudor age. It is estimated that during the reign of Henry VIII, around 72,000 people were executed.

“In the late 1700s, over 220 crimes could attract a death sentence under the Bloody Code”

In this period, capital crimes were many and varied often involving petty theft. Methods of execution varied according to your class. The upper classes could expect to be beheaded but others were not so fortunate. Treason was punishable by hanging, drawing and quartering for men and by burning alive for women. You might also be burned for blasphemy, heresy, witchcraft and marrying a Jew. Boiling to death was another approved punishment in the 16th century.

By the late 18th century the English legal system, often referred to as the ‘Bloody Code’, established over 220 crimes in Britain that could attract a death sentence, including cutting down a tree, stealing from a rabbit warren and being out at night with a blackened face. The purpose of such harsh punishments was often to protect the property of the wealthy (who also made the law) and the gruesome methods of execution, often carried out in public, were aimed to deter and terrorise the populace into obedience.

Here Philip I of Spain is shown watching the burning at court of a heretic who did not believe in Catholicism. This print shows a scene from a story called Auto-da-Fe from The Ingoldsby Legends published by Richard Bentley in a series of works in the 1840s.

Early reform

During the 18th and 19th centuries, as modern nation states started to come into being and the rights of men became a serious concern leading thinkers began to question the ethics of the death penalty. Most notably Italian criminologist and politician Cesare Beccaria wrote a thorough analysis of the death penalty in 1764, noting that it was often counter-productive.

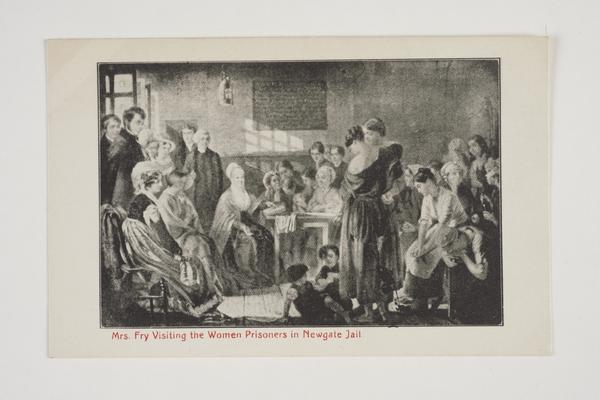

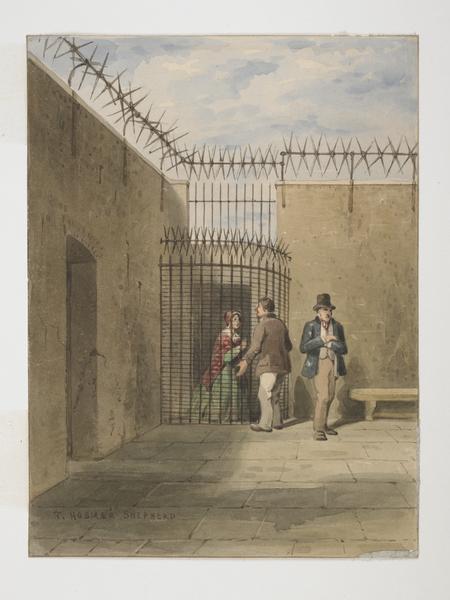

In the late 18th century, penal reformers such as John Howard looked to the prison system as an alternative punishment to execution with the potential to reform criminals. Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry – while never openly campaigning for the complete abolition of the death penalty – supported the female prisoners at Newgate Prison, and was influential in the passing of reforms.

Elizabeth Fry was among the several penal reformers who supported the female prisoners at Newgate Prison, and was influential in the passing of reforms.

During the early 19th century, Britain removed the death penalty for a wide range of crimes, including pickpocketing, forgery and rape. By 1861, the number of capital crimes had been reduced to five, including murder, treason, espionage, arson in royal dockyards and piracy with violence. Other reforms included the banning of public executions in 1868, and the abolition of beheading and quartering in 1870. The age at which a person could be executed was also raised first to 16 and then 18 in 1933.

Modern reforms

Prior to World War II, an attempt was made in Britain to abolish the death penalty, but the outbreak of war, defeat in the Lords and fears about public reaction caused the government to shelve the proposal. In 1957, public doubts about high-profile cases such as Timothy Evans and Derek Bentley eventually led to the 1957 Homicide Act that reduced the categories of murder that could be punishable by death. In 1965, the death penalty for murder in Britain was suspended for five years and in 1969 this was made permanent. However, it was not until 1998 that the death penalty in Britain was finally abolished for all crimes. The last people executed in the UK were Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans on 13 August 1964.

“10 October is observed as the World Day Against the Death Penalty”

Around the rest of the world, the picture varies enormously, but the direction of travel is clear. In 1977, only 16 countries had abolished the death penalty in law. Since then, more and more countries have recognised that the death penalty is both cruel and ineffective and have either called a halt to executions or abolished the death penalty in law. Since 2003, 10 October has been observed as the World Day Against the Death Penalty. The purpose is to bring together the abolitionist movement and to raise awareness around the world that the death penalty still exists and the terrible conditions and practices endured by many citizens in countries that retain the punishment.

The position today

Amnesty International, which opposes the use of the death penalty in all circumstances, publishes an annual report on the use of the death penalty throughout the world. In its 2021 report, Amnesty found that 108 countries had entirely abolished the death penalty and a further 44 had abolished it in practice. Only 55 states retain the death penalty in practice.

The number of recorded executions has also fallen markedly as has the number of recorded death sentences. Another area of progress has been the creation of international standards relating to the death penalty. Unfortunately, not all countries abide by these standards.

International law also states that the death penalty should be reserved only for the most serious crimes of intentional killing. However, other crimes for which you may suffer the death penalty in some countries include drug-related offences; economic crimes such as corruption; blasphemy; rape; and treason or opposing the state.

You can even be sentenced to death for engaging in same-sex relationships in several countries.

Execution broadside printed with an account of Henry Fauntleroy's crimes, trial and his last days in prison before his public execution in November 1824.

Amnesty International’s position

Amnesty International is one of the several organisations that oppose the death penalty with no exceptions. The reasons for this are many, including, there is no good evidence that it is a significant deterrent; the certainty that innocent people will be executed; it is not (as some claim) cheaper than a life sentence (not that saving money is a reason for killing people anyway); it is discriminatory (racial and other minorities are often the most targeted); the penalty’s use in conjunction with unfair legal systems (unfair trials, conviction in absentia, ‘confessions’ obtained through torture); its use as a political tool to repress political opponents; and most importantly, the moral objection — killing people is wrong.

Amnesty campaigns around the world against the death penalty and our campaigns include encouraging and lobbying countries to halt executions and abolish the death penalty. We also lobby with UK ministers and MPs to raise concerns when visiting countries that still have the death penalty. Our urgent actions include mobilising Amnesty members and the public to call and petition for stays and exonerations.

The author, Paul Bridges, was interviewed for a documentary as part of the exhibition ‘Executions’, which ran at London Museum Docklands, until 16 April 2023.