05 July 2024 — By Máire MacNeill

Embroidered memories: The First World War silk postcard industry

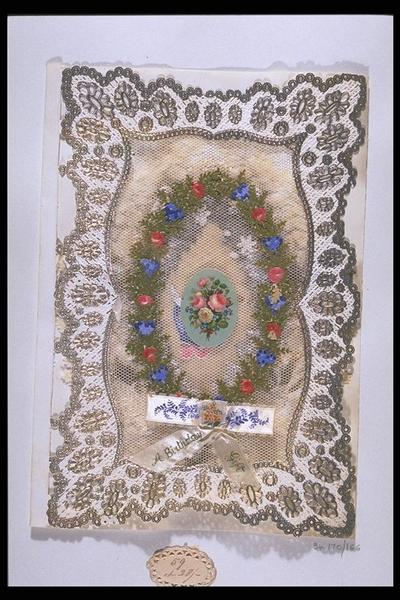

These First World War silk postcards conveyed messages between soldiers and families. Handcrafted by women embroiderers near the front lines, they are beautiful examples of sentimentality and wartime industry.

During the First World War, homesick soldiers on the front lines sent beautiful silk postcards to their loved ones at home. Embroidered with sentimental phrases such as “Yours Forever” and “A Kiss from France”, the colourful flowers, butterflies and other symbols of peace and hope contrast with the mud and squalor of the trenches. They allowed soldiers to send simple messages of longing to the families they had left behind.

Many of these postcards survive today in private collections, as family memorabilia and in museum collections such as ours. However, what many don’t realise is that these beautiful souvenirs are not only examples of sentimentality during difficult wartime but also craftsmanship, along with mass production and industry.

The hand-embroidered silk pieces would be framed with card paper, with some brief messages on the back. Sometimes with a pocket created to hold a note, and at times a card would be left empty and framed by those at home for display and memory, as many of those who sent these souvenirs, probably never made it back home. Their delicate craftsmanship concealed the appalling conditions faced by soldiers living in the trenches and protected their loved ones from the reality of a brutal war that killed so many.

How were these First World War silk postcards made?

The majority of postcards manufactured during this period were made by women living in towns near the front lines in France and Belgium. They saw an opportunity to use their embroidery skills to produce these beautiful gifts for soldiers.

Although the postcards were handstitched, they were produced en masse. Patterns were repeatedly embroidered on long strips of silk mesh by women working at home. Once completed, they were sent to factories in cities such as Paris for finishing. There, they were cut into individual pieces and mounted onto postcards. At this stage, embellishments could be added – for example, some postcards had a pocket that would open to reveal an embroidered silk handkerchief folded carefully inside as a gift to the recipient.

These silk cards were not cheap. Paper and ink shortage during the war had pushed up their price, and combined with the costs of silk and labour, the postcards could cost between 1 and 3 francs. This was about a day’s pay for many low-ranking soldiers.

Despite the relatively high cost, silk postcards were an attractive purchase. Throughout the war, as many as 10 million cards were manufactured, suggesting that there was a steady market among the servicemen at the front.

Historical origins of the silk postcards

These silk postcards were not a wartime invention. They could be found in France and Belgium since the early 1900s. Popular embroidered patterns included flowers, shields and flags sent as tokens of love.

An earlier version could be found in the late 19th century by a weaver Thomas Stevens from Coventry, who adapted Jacquard looms to create pictures woven with silk. Called Stevengraphs after its inventor, early examples primarily included decorative images like landscapes, celebrity portraits and bookmarks. He started manufacturing silk postcards in the early 20th century, and the business continued until 1940 when the factory was destroyed in the Blitz.

Why were silk postcards popular among soldiers during the First World War?

Many of these postcards survived in family collections following the war and have subsequently been donated to museums as a poignant reminder of the devastating impact of the war. These simple messages may have been the last contact those back home in England had with their fathers, sons, brothers, husbands and lovers.

Very rarely do the postcards indicate the true horror faced daily by the soldiers on the front line. But while the messages remain simple, they reveal how loved ones back home in ‘Blighty’ were never forgotten. Most of the postcards in the Museum of London’s collection refer to Christmas or birthdays, suggesting that many soldiers preferred to send them on special occasions. However, one soldier is known to have sent 210 postcards home to his fiancée during his time overseas.

Occasionally, a group of postcards from the same sender allows us to find out more about who he was. Three postcards in the collection, written in the same handwriting, were sent to a son and a daughter at home in London for birthdays and Christmases. There are several such examples of cards to children and with special notes for wives.

“Soldiers likely included these postcards with other letters and packages they sent home”

Two such postcards include a name and address. Using this information, we looked up census records to find the name of the soldier who sent them – John Stephen Lister. Before the war, Lister was a Police Constable living in a three-room property in Kensington with his wife Hettie, two children Florence and John, and extended family members. The 1921 Census confirms that Lister survived the war and continued working as a Police Constable, living with his family in Paddington.

Memories and keepsakes

Unfortunately, unlike the ones from John Lister, most of the postcards in our collection do not have a handwritten address on them, which can make it difficult to trace who sent them. Soldiers likely included them with other letters and packages they sent home, which would have also helped prevent the embroidered patterns from becoming damaged. Others left completely blank, may have been bought as keepsakes of a soldier’s time at the front.

Although this lack of information makes it difficult to trace the servicemen who sent the cards, the messages remind us of how important they were for soldiers and their families. Take, for instance, a card embroidered with the words “Home Sweet Home”, with the following message on the back: “Annie, What I am thinking of after getting your letter.”

Although the Stevengraph Works survived until 1940, the silk postcard industry saw a steep decline after the end of the war, once the servicemen who had been the chief customers returned home. However, many of the postcards were preserved in families for years afterwards, not only as a testament to the strong sentiments between loved ones separated by war but also to small industries such as this one that flourished because of the war.

Máire MacNeill is Project Assistant (New Museum) at London Museum.