16 November 2022 — By Simone Few, Simon Jarrett

Disability, as seen in 18th-century art

As we improve our representation of disability histories in the London Collection, we train our focus on four artworks from the 1700s – which is when London was expanding in size, population, wealth and power.

How were disabled Londoners portrayed?

Here at London Museum, we tell the stories of Londoners. However, we appreciate that there are many Londoners who have been under- or misrepresented in those stories over time. For example, the experiences of disabled Londoners throughout the city’s history has been rarely explored. This is quite startling, considering that impairment has always been an integral part of human life.

“These stories and representations are far from hidden – they are often right there”

While there is much research and collection work to be done to improve representation, it is important when discussing disability histories to highlight the wealth and richness of the stories we already have. Mistakenly thought of as a ‘hidden history’, these stories and representations are far from hidden – they are often right there, in front of us! We simply need to train ourselves to see.

In order to demonstrate that these stories exist in abundance (when not overlooked), we trained our focus on a very narrow part of London’s history from our collection. The 1700s seemed a good place to start – the city was expanding in size, population, wealth and power. How would we get on?

‘Hidden’ in plain sight

It didn’t take very long before a wealth of potential examples came tumbling out. First are these two William Hogarth engravings. Southwark Fair (1733) illustrates many aspects of a typical London street fair of the early 1700s. In The Idle ’Prentice Executed at Tyburn (1747), Hogarth takes us to a public execution. Both give the viewer a sense of the everyday people, activity and noise of London streets of the time.

In Southwark Fair, we can see, in the bottom-left corner, a man of short stature playing the bagpipes. Opposite, just by the horse's head, stands another person of short stature with their back to us, playing a drum. In this engraving, Hogarth makes it clear they are part of London — everyday individuals living their lives in the city.

We do need to explore the nuanced topic of people whose unusual bodies have provided them with a way of earning a living, as these two people are likely doing at the fair. This is a difficult topic to discuss. While so-called “freakish” displays could be seen as exploitative and objectifying, they were also areas of entertainment in which disabled people could be entrepreneurial and in control of their own lives. Newspaper advertisements from the time survive in huge numbers for individuals such as John Coan, the ‘Norfolk Dwarf’.

Coan arrived in London in 1752, and became very popular, regularly appearing in taverns and for royalty. It was a way of making money — people could profit a lot from their unusual bodies, but perhaps at a cost of their personal dignity. It is also tricky to understand this against a society that was arguably more at ease with disabilities than we are today. The risk of disability from birth, accident or illness was much greater, and, therefore, disabilities themselves more common and accepted.

In The Idle ’Prentice Executed at Tyburn, there is a very clear depiction of a man with a crutch (left foreground). It is fashioned in a V shape so that his knee can rest in a bend of the stick while providing the man with stability. Tyburn was on the outskirts of the city, demonstrating this man’s ability to traverse the city. Assistive technology like this crutch are testament to the amazing adaptability and ingenuity of humans over the centuries to navigate their environment.

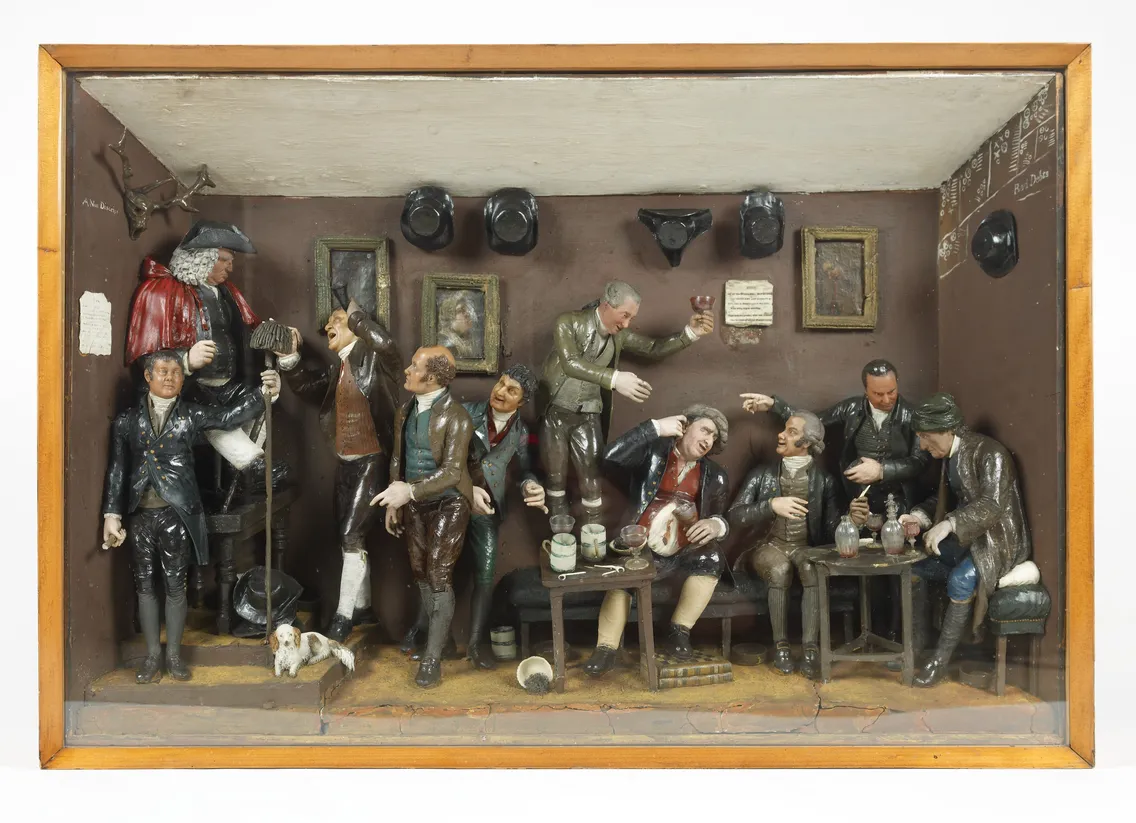

Another example from a similar time period is in a wax diorama of London’s famous Literary Club from around 1785.

Listening in with an ear trumpet

The influential Literary Club was founded in 1764 by the English portrait painter Joshua Reynolds, who had become partially deaf as a young man. One of the club’s core members was Samuel Johnson, who famously compiled A Dictionary of the English Language (originally published in 1755).

In this diorama, you can see Reynolds, behind the dog, listening to Samuel Johnson with an ear trumpet. This early hearing aid funnelled sound into the eardrum. It would have been a way for Reynolds to hear Johnson more easily over the hubbub and chatter at the club. Although technology has improved today, this diorama shows that the desire for humans to use something to navigate their daily lives more easily has always been there.

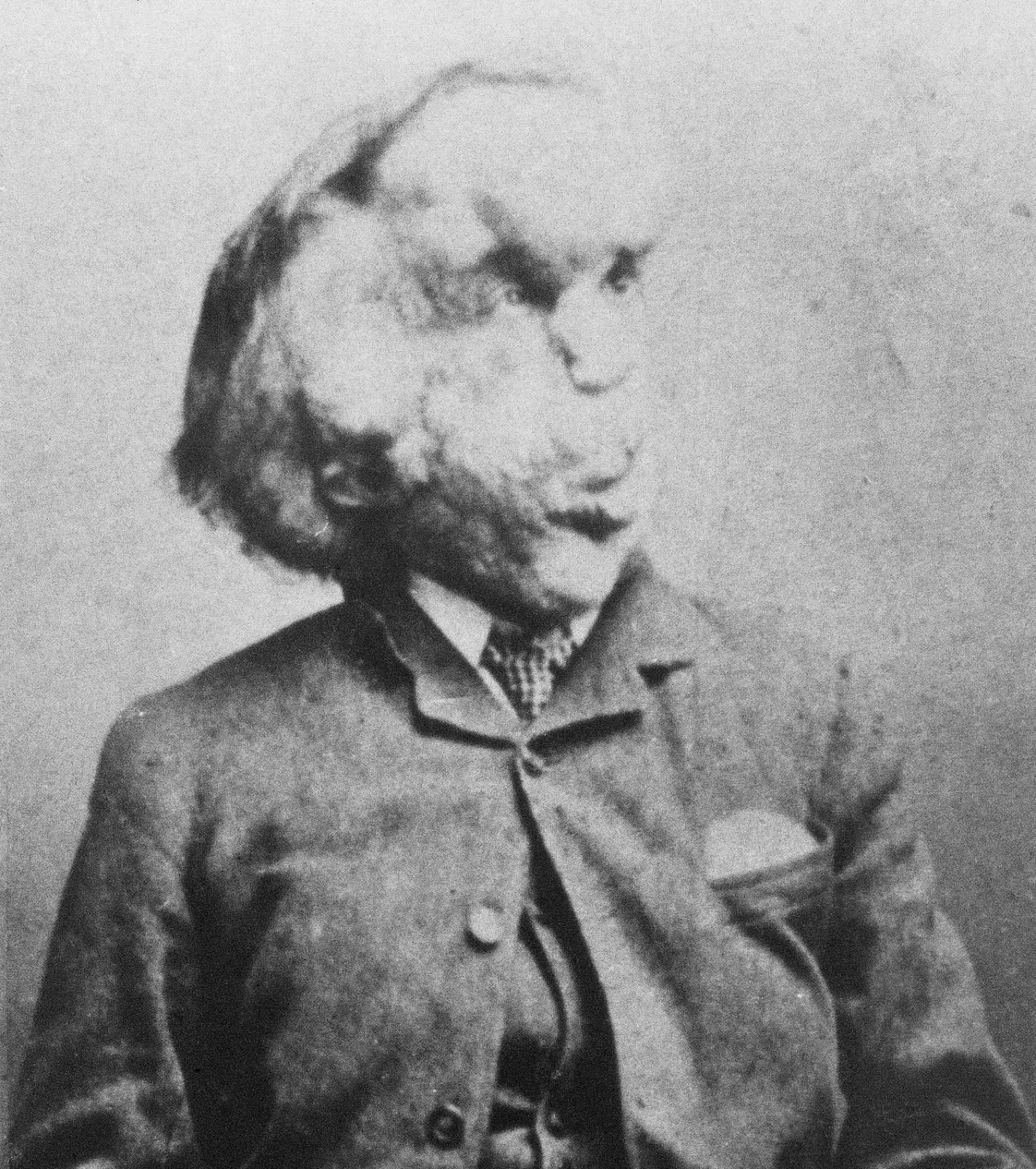

Hidden disabilities

It is also important to explore Samuel Johnson a little further here. Many researchers believe he had depression throughout his life and, possibly, also had what we would understand today as Tourette Syndrome. Although this is a retrospective diagnosis – Johnson could not have described himself, or been described by others, using these modern terms – it is an important opportunity for us to explore non-visible disabilities. It’s very easy for us, as examples highlighted here have shown, to pick out physical disabilities. But, in order to be representative of all Londoners, we should also strive to seek stories of disability which are not immediately apparent.

“The ‘Social Model’...says that people are disabled by barriers in society...and not by their impairment or difference”

This might be a good place to briefly touch upon the ongoing conversations around ‘what do we mean by disabled?’ Traditionally there has been a focus on the ‘medical model’ where people are defined by their impairments. But now the conversation has widened to include the ‘Social Model’, which says that people are disabled by barriers in society (such as inaccessible buildings) and not by their impairment or difference. This places responsibility on society to be more inclusive.

Disability and the workplace

This painting by an unknown artist shows a blind woman selling curds and whey on Cheapside. (ID no.: 82.338)

“People with disabilities in the 1700s worked, were expected to work, wanted to work, and had...networks that enabled them to do so”

Another example of 18th-century Londoners in their workspace is this beautiful painting of The Curds and Whey Seller, Cheapside, 1730, by an unknown artist. It depicts a young blind woman, selling curds and whey in Cheapside. There is much to be said about the symbolic undertones of her clean and saintly appearance, in contrast to the soot-covered and potentially mischievous chimney sweeps next to her.

This addresses the social hierarchy at the time, making clear that this woman with a disability is not at the bottom of it. But more importantly, this painting shows that people with disabilities in the 1700s worked, were expected to work, wanted to work, and had interactions and networks that enabled them to do so.

Increasing representation in our collections

Here, we have focused on just a couple of examples from 100 years of London’s history from our collection, and found plenty of Londoners living with disability and getting on with their lives. There are many more to discover.

Skip forward to the 1800s and you can find a wonderful mug with British Sign Language instructions on the side. Keep travelling on in time and you’ll find how our modern collection practises are changing to ensure we actively involve stories of disability in our collecting. We are starting to hold ourselves more accountable for the stories we tell, to ensure that the 3 in 20 Londoners who are living with a disability, see themselves in the city’s history. In many cases, these stories are right in front of us but, as with many Londoners who experience disabilities today, simply overlooked.

Simone Few is Audience & Interpretation Lead (Exhibitions and Displays) at London Museum and Simon Jarrett is Advisor on Presentation of Disability History.