22 January 2024 — By Simone Few

Disability: A child’s perspective from 1950s London

These Henry Grant photos of disabled children in specialist schools in 1950s London attempt to fill a crucial gap in documenting our history and the fight against ableism.

Stories of disability are often under- and misrepresented in museums and collections. This is despite the fact that a wealth of such stories have existed, and continue to exist around us. Such negligence is more acute while recording first-hand experiences of children, as they have to get past adult gatekeepers before they’re heard or valued.

But a collection of Henry Grant photographs from the 1950s when he visited two specialist education schools, allow us a peek into the lived moments of disabled children. These are the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Physically Handicapped School (FDR School) in Hampstead, and Ackmar Road School in Parsons Green. We also have some oral histories of adults who share their childhood experiences of disabilities, where their stories come to light.

These recordings and photos allow us to explore the history of specialist education in London. We discovered stories of prejudice, but also joyfulness.

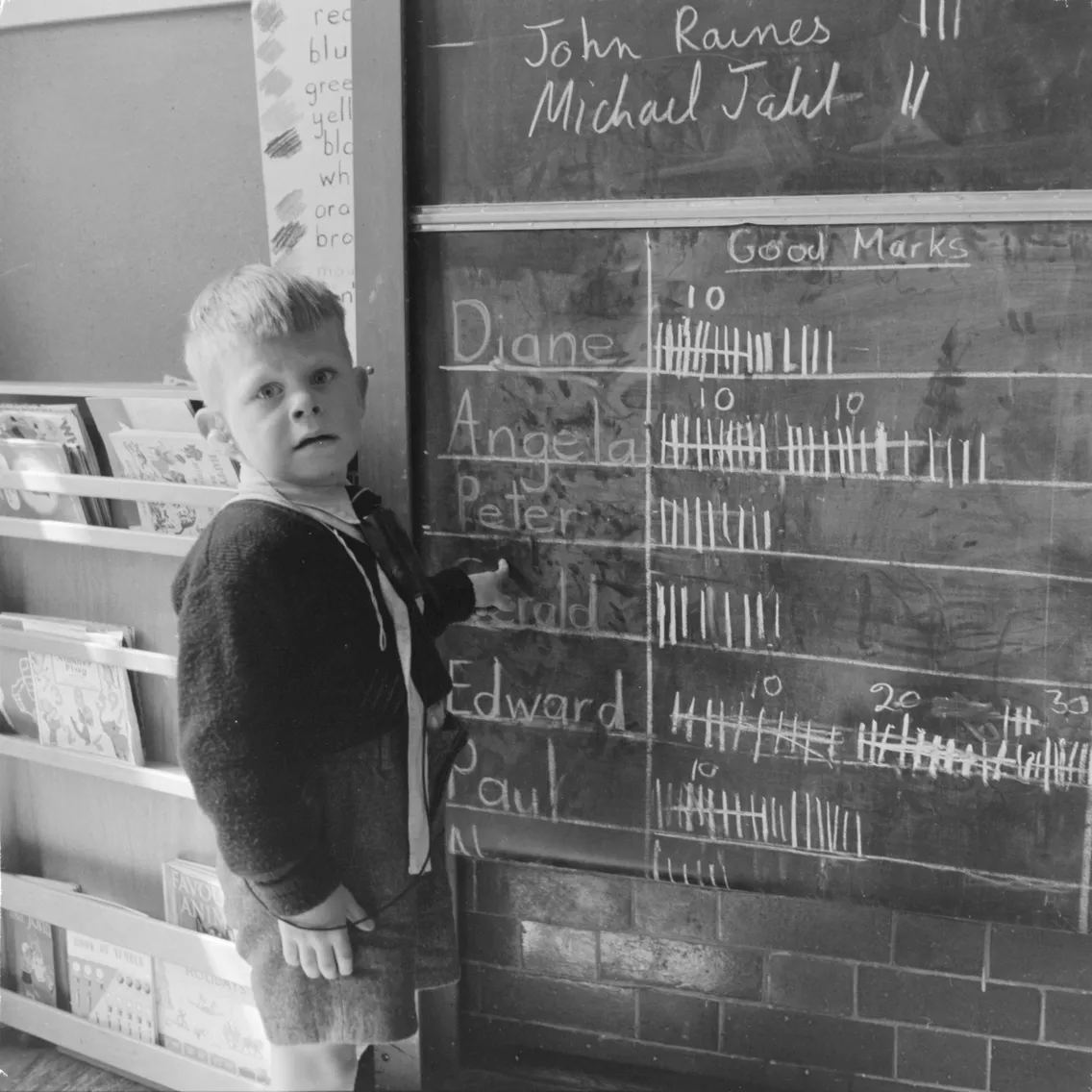

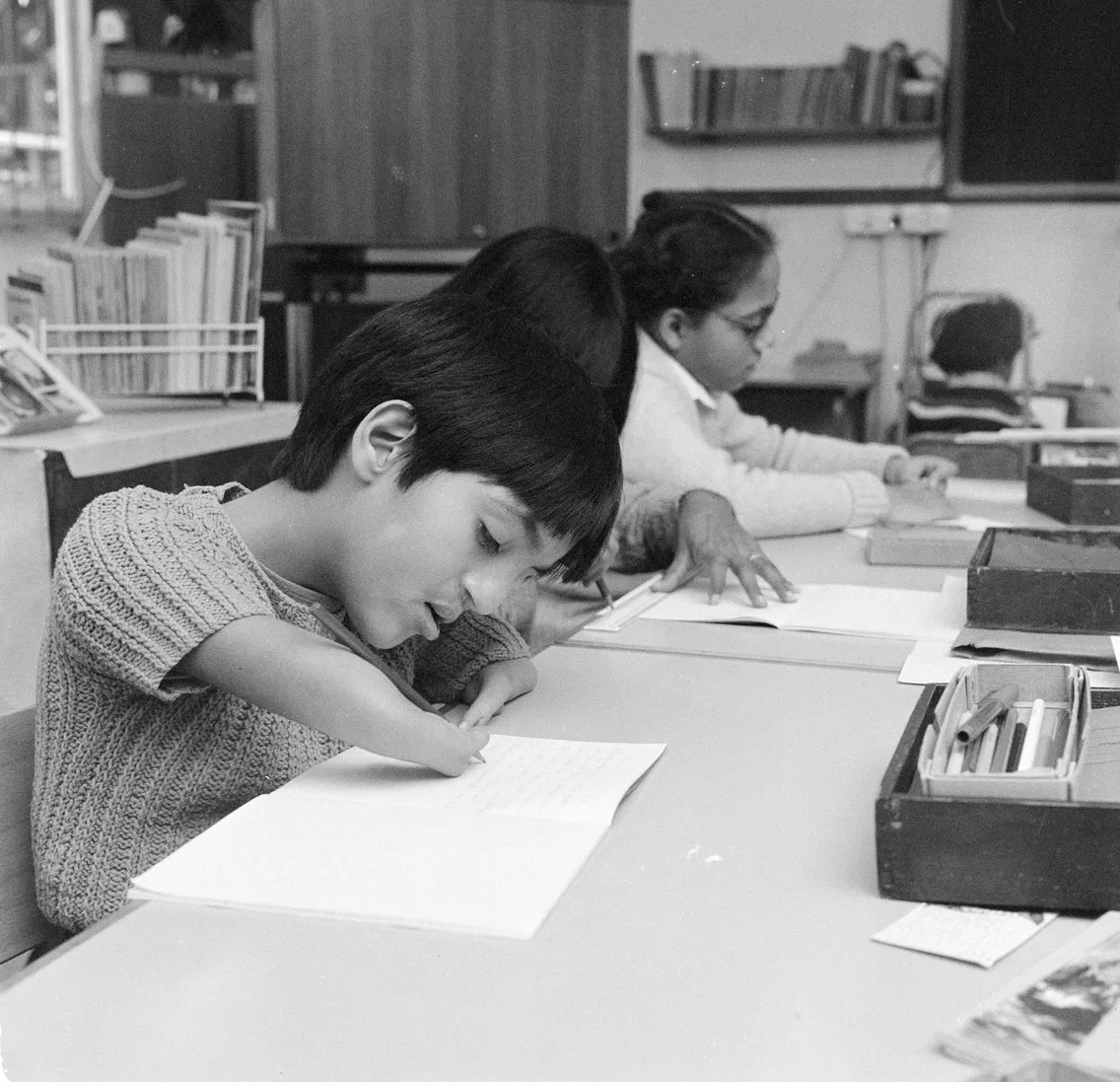

Henry Grant’s photos of disabled children at school

Two pupils concentrate on their sewing work at the Franklin D Roosevelt School in 1957.

Ackmar Road School for Deaf Children in Fulham, later known as the London School for the Deaf, opened in 1898, where pupils could learn with the assistance of hearing aids and other technology.

The FDR School opened in 1950 for physically disabled and seriously unwell children. The name was later changed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt Special School, dropping the derogatory term ‘handicapped’. It was designed over one storey and prepared pupils for independent life. Girls learned skills such as dressmaking and domestic service. Boys could do carpentry, basket making and shoemaking.

“Photographs can still hold many biases, of course, however, they are at least coming directly from the children”

The photographs by Henry Grant in the museum’s collection have proved very useful in our search for lived experiences of disabled children. Grant was skilled at capturing spontaneous, candid moments. This approach is great – and necessary – to see glimpses into the children’s experiences at these schools. The photographs are not stiff, formal portraits but catch fleeting moments and gestures. Photographs can still hold many biases, of course, however, they are at least coming directly from the children.

A 1959 film, The Silent Hope, similarly captures the education of the deaf children at three London schools, including the Ackmar Road School. While the narration and tone are compassionate, they are also complimentary to the ableist approach – prioritising the needs of non-disabled people – which is worth keeping in mind. The film is free to watch on the British Film Institute website.

The first specialist education schools in London

The photographs from the FDR School were taken during the opening week of the new light-filled, step-free building surrounded by lawns and trees built by the London County Council in 1957. Specialist education centres like these were not a new thing for London.

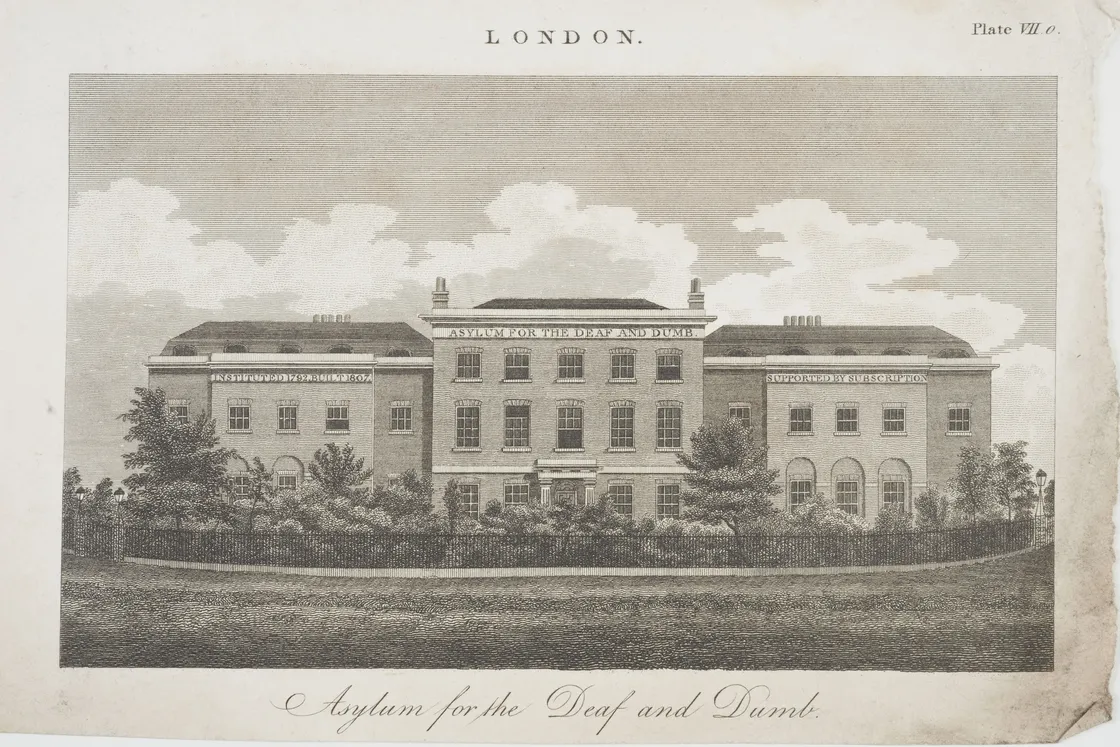

Thomas Braidwood had set up Braidwood's Academy for the Deaf and Dumb in Hackney, east London, in as early as 1783. One of its pupils, John Creasy, was instrumental in the building of another school, the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, in Bermondsey in 1792. This became the first public school for the deaf in England. Starting with just six children, its success lead to a larger school opening on Old Kent Road in 1807, which had space for 200.

“By 1899 there were 43 specialist education schools in London... Now the number is nearer 2,000”

Another indicator of the importance of sign language for kids at the time is the mass production of children’s ware, such as mugs and plates, with letters and finger spellings transfer-printed on them. The museum has three sherds from such a cup, and another more recent example from the London-based Breakthrough Deaf-Hearing Integration.

By 1899 there were 43 specialist education schools in London, teaching around 2,000 disabled children. Now the number of schools are nearing 2,000.

London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, in Bermondsey in 1792.

Ableist education for disabled children

In 1918, specialist schooling for disabled children became compulsory. While this was a huge step forward, the estimated half-a-million boys and girls who had a physical disabilities or sensory impairments in this period still experienced an ableist education.

A photograph from Ackmar Road School features deaf children being taught to speak and lip-read using hearing aids and induction loops. This photo is significant when contextualised with the priority given to communicate with hearing individuals, rather than using means such as British Sign Language (BSL) to communicate with their non-hearing community.

Interestingly, this is the opposite of the approach Braidwood had in his schools in the late 1700s, where sign language was encouraged.

Unfortunately, in 1880, an international conference of deaf educators in Milan – in which there was only one deaf delegate – declared that oral education was superior to sign language. Deaf pupils were told to prioritise speaking with hearing individuals, rather than their non-hearing peers.

This type of ableism was immensely damaging to the deaf community and its impact was felt at all levels of daily life, including education. An official apology was made by the board at an International Congress on Education of the Deaf in 2010 accepting this as an act of discrimination.

Disabled children also experienced ableist expectations of what they were capable of. In many schools, the focus was on soft skills, in the belief that they would be lucky to secure any sort of job at all, rather than aspiring to the same levels of education of other school children.

These schools were also a form of segregation. Only a small number of children were permitted to remain in mainstream education. Even within living memory, it was often thought better for children to be away from their families for their education, so for many their experience was residential.

Experiences of disabled children today

Many things have changed in recent years. To understand a little more about what more modern childhood experiences were for Londoners, we reached out to our Disability & Inclusion Staff Network.

Clare Baker, our Visitor Experience Training and Development Coordinator says, “From my perspective, it was a great advantage to be able to go to the local school and the same school as my siblings in the 1980s to mid-1990s. I was able to utilise the full range of education including taking GCSEs and A-Levels.”

“I did feel a bit of the odd one out and thought potentially teachers had lower expectation of my academic abilities...”

Clare Baker, Visitor Experience Training and Development Coordinator, London Museum

“I did feel a bit of the odd one out and thought potentially teachers had lower expectation of my academic abilities. One memory was of my art classes where the teacher had been assuming my support worker completed work on my behalf. When one day my support worker was sick the art teacher was obviously shocked when I produced a high-quality piece of work ‘unaided’.”

“They didn’t have the resources to teach me Braille, which would be a standard skill taught in a school for blind children. Overall, the school did the best job they could considering their potential lack of specialist training, resources and awareness”.

We looked through oral history recordings of people recounting their childhood in museum’s collection, and came across an interview with one Stanley Rothwell from 1979-1980. He recounts this experience from his early years: “And this inspector came along…he said ‘Say niney-nine’. I said ‘ninety-nine’. He said, ‘Again’, I said, ‘ten’, because I’m hard of hearing you see and everybody laughed at me.”

A child speaking into a microphone at the Ackmar Road School for Deaf Children, 1958.

In their own words

Accounts by Baker and Rothwell show why it is powerful to have document stories directly from children. We need to have greater representation in their own voices. This is something the museum is addressing in our three-year project, Young Londoners Archive.

The quest for equality and inclusion is ongoing. And these photos by Henry Grant reinforce why museums play an important role in the fight against ableism. By continuing to unearth stories from disabled Londoners, London Museum, like many others, is doing its part in growing that collection for the future.

Simone Few is Audience and Interpretation Lead, New Museum, at London Museum.

Did you go to Ackmar Road School or the FDR Special School? We are featuring stories about these schools in London Museum at Smithfield, and would love to hear about your experiences. Write to us at [email protected] to share your story.