20 January 2020 — By Echo Godfrey-Simson, Emily Austin

Conserving Una Maw's famous 1920s Vegetable Dolls

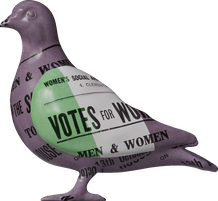

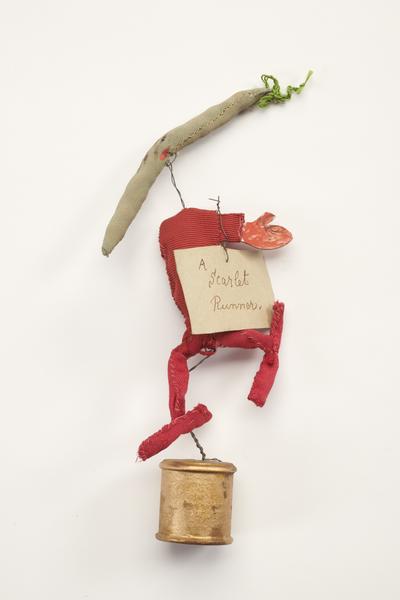

Find out what goes into the restoration of these 1920s’ amazing handmade Vegetable Dolls depicting a range of extraordinary characters by Una Maw.

Textile conservation student Echo Godfrey-Simson explains how she helped conserve these century-old dolls:

During my student placement in London Museum’s conservation department, I had the opportunity to practise my skills on the museum’s collection of vegetable dolls. These were handmade by author, painter and poet Una Maw at home about 100 years ago. Nine of the 34 dolls in the museum’s collection were on exhibit, alongside a book written by Una in the museum’s 2019 ‘Collecting for London’ display.

The conservation of the dolls was carried out in consultation with curator Lucie Whitmore and textile conservator Emily Austin. They made sure that all of the conservation treatments we carried out were appropriate and maintained the original significance of the dolls.

Assessing the dolls for conservation

I began by carrying out a condition assessment of the chosen dolls, which varied widely in terms of their preservation. On first impression, the padded cloth dolls appeared in fairly good condition, but on closer inspection, several had damage or weakness to their garments or accessories. This is most likely to have come from insect attack, accidental damage during use or the chemical degradation processes that are inherent to textiles as they age. Those dolls which were not going on display were also treated ahead of photography to be shown alongside the display.

Many of the dolls simply required surface cleaning to remove dust and particulates, such as loose fibres, that have built up over time in storage. They also needed humidification to reduce some sharp creases. As well as looking unsightly for display, these creases could lead to future damage if left in place.

Surface cleaning and removing creases

We carried out surface cleaning with a low-suction vacuum and dry cosmetic sponges. The name tags on the dolls were cleaned with a ‘smoke sponge’ (dry rubber-based sponges), based on advice from London Museum’s paper conservators. This helped reduce sooty soiling on their surface.

We reduced the creases with a combination of ultrasonic (cold steam) humidification and contact humidification. These are both methods of introducing water vapour into the textile which encourages the fibres to relax without needing to get the textile wet.

Choosing the right fabric and technique

A number of the dolls had other conservation needs for us to address to make them fit for display. There were areas where fabric had worn away, been damaged or degraded. We supported these with patch supports in silk or cotton, which we stitched into place with laid couching.

One of the dolls, Lord Leek, had an old repair to his trouser leg which was pulling and distorting the fine silk of the trousers as well as the padded leg underneath. Following humidification and surface cleaning, the next stage of his treatment was to remove this repair and infill it with a more supportive patch.

Choosing the most appropriate textile fibre, colour and finish for the patch and thread is an important part of the conservation process. If these materials are unsuitable it will attract attention to the area of damage rather than mask it. As fabric is not sold readily in every shade required, textile conservators often dye their own fabric to match. As there was no suitable previously dyed silk in the studio in this instance, I set to work trying to match the trouser colour.

This was achieved by mixing two or three conservation-grade dye colours in varying quantities and proportions until I was able to create a colour that matched the depth and shade of Lord Leek’s trousers.

Using the newly dyed silk, I carefully inserted a small patch under the trouser fabric and stitched it into place along the seam and hemlines. Due to the fragile nature of the purple silk, I chose a dyed nylon net overlay to minimise stitching.

Creating the correct mounts for display

Textile conservator Emily Austin explains the process of readying the dolls for display.

Working with our in-house technicians, we created custom-made mounts for each doll using acrylic bases and coated wire supports. Each doll had different requirements for the level of support needed. Some were top-heavy having larger heads, requiring stronger wire support and others had very thin necks held only by some stitching.

Mademoiselle French Bean had a wobbly top, heavy head and fragile blue ribbon on her back. Her mount was extended to support her neck and reinforced with loops of fine polyester thread. The mount sat away from the body, resting under the arms to avoid placing any pressure on the silk ribbon.

Lord Cucumber had similar issues, as his tunic and trousers although conserved remained fragile. His mount was designed to support his body from the underside of his head (being a sideways cucumber shape) and, therefore, avoiding pressure on his fragile textile clothing.

Displaying these dolls almost a century after they were donated to the museum by the creator herself not only gave the museum’s conservators a chance to restore them, but also readying them for any plans to display them in the future. They showcase not only Una’s fascination with India but are a testament to the textile history of the subcontinent.

Echo Godfrey-Simson is a textile conservation student, and Emily Austin is Textile Conservator at London Museum.