21 March 2022 — By Jasmine Pierre

Brixton 1981 to BLM: Reflections on Black uprisings

Listening to London volunteer Jasmine Pierre discusses oral histories of the 1981 uprising in Brixton to reflect on her own experiences of racial upheavals in London in 2011 and 2020

How do oral history collections come into being? How do they represent political moments in London’s history? And do they stand the test of time?

In the context of the Listening to London project, I explored London Museum’s ‘Brixton Riots’ collection that was recorded in 2009. When I started working with the collection, I immediately recognised that the use of the term ‘riot’ in its title was problematic. It implies that the 1981 Brixton uprising was intentionally aggressive and unreasonable when, many would argue, it was inevitable and even a fundamentally necessary response to the injustices suffered by Black and Brown communities in London.

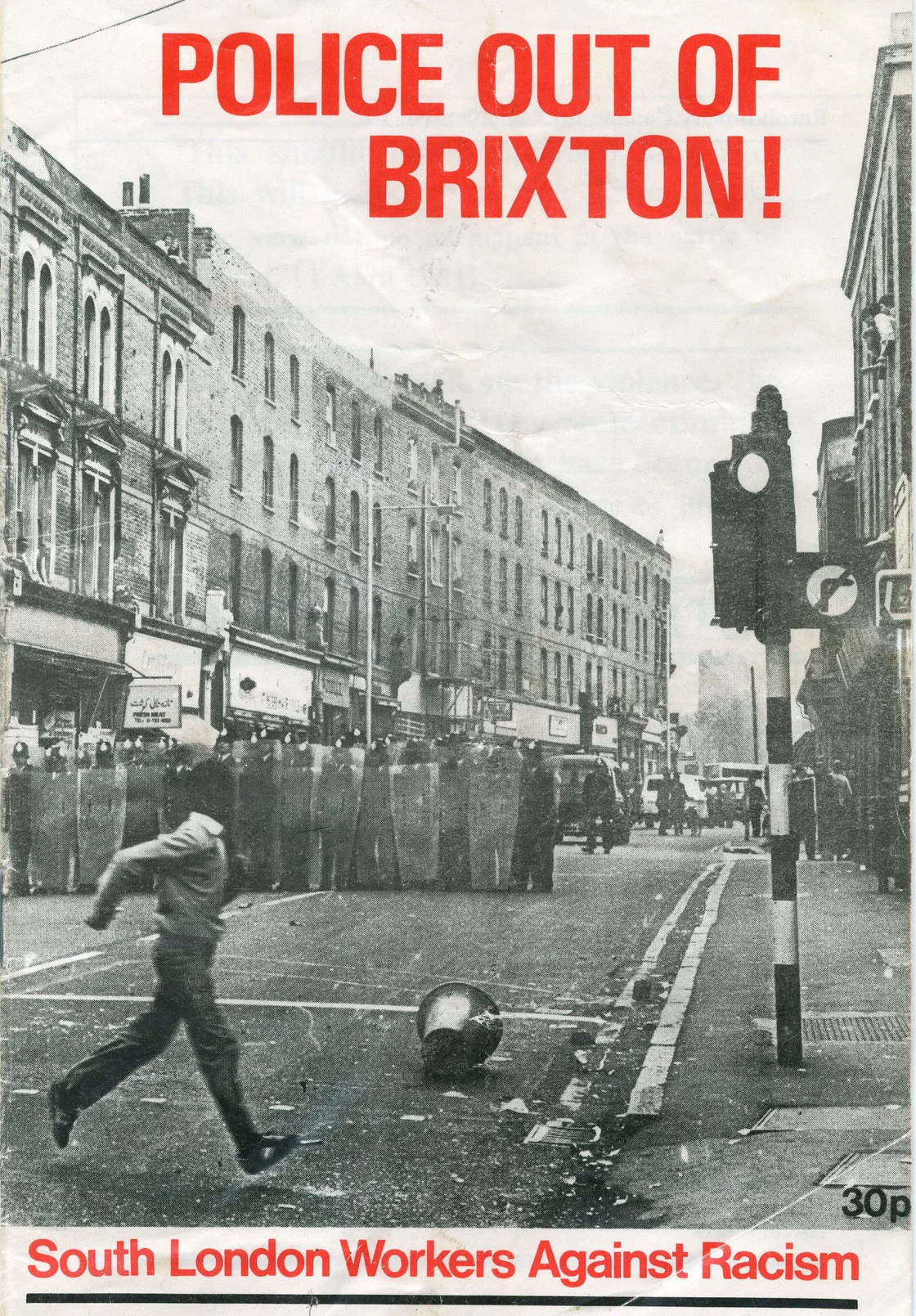

'Police out of Brixton' leaflet, 1981, with the words South London Workers Against Racism.

Remarkably, the museum’s oral history collection is filled with the perspectives of white ‘authoritative figures’, such as police cadets, speaking about this moment, and Black voices are relatively underrepresented. Some of the interviews also consistently use subtext, for example, by using the word ‘different’ to describe Black people within the area. The problem with this unbalanced representation is that such prejudiced views dehumanise and ‘other’ Black communities, and that Black people are inhibited from having autonomy over their own history, ultimately alienating them from being part of British society.

In the interview with Bernard Willis, he talks about growing up in London and becoming aware of ‘different people’.

“As I was growing up, you became aware of different cooking smells…”

Bernard Willis

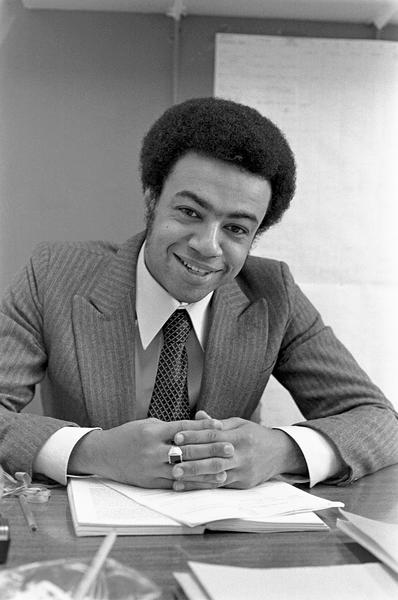

The changing nature of uprisings

However, I came across a fascinating interview with Alex Wheatle, a prominent British author who has written many novels, including young-adult fiction, drawing on his own life experience. He participated in the Brixton uprisings and was imprisoned. The interview is rich in his experiences, thoughts and emotional responses to the uprisings. It became a starting point for me to reflect on my own memories of Black resistance in London during my lifetime. I am a 22-year-old mixed-race woman, specifically white and Black Caribbean, based in Balham, south London, where I have always lived.

I have spent a lot of time in different areas of South London, and currently work at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton. The main uprisings by the Black community I have witnessed are the 2011 uprisings, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in 2013 and their resurgence this year (2020).

An interesting point of connection between Wheatle’s experiences and my own is that of the physical damage caused by the uprisings. I have witnessed the lingering physical effects on neighbourhoods and how they affect communities long after the uprisings are over. But the nature of where this physical damage happens, and why, has changed between 1981 and 2020, shifting from the destruction of local areas to statues and places that embody power and oppression.

Main causes of the 1981 Brixton uprising

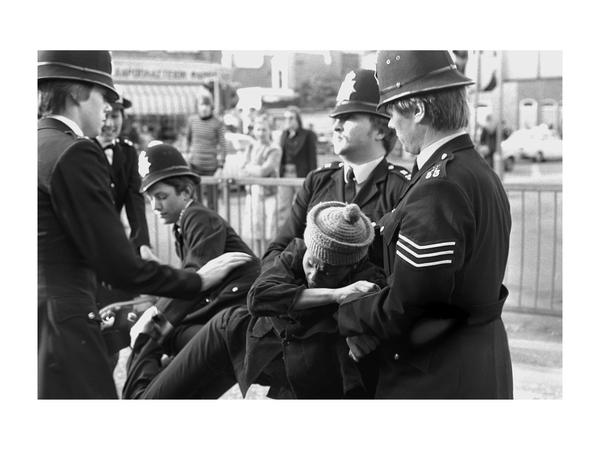

The 1981 Brixton uprising was caused by several factors, including social and economic deprivation. A prominent factor was growing tensions between the Black community and the Metropolitan Police. One of these was discrimination through the stop and search (‘sus’) law that enabled the police to stop anyone they deemed acting suspiciously, essentially enabling racial profiling. Another factor was the inadequate police investigation of the New Cross Fire several months earlier. The Brixton uprising of 1981 remained fairly localised and the local area suffered heavy damages.

Wheatle describes the different elements of this physical damage and highlights the complex nature of the destruction, noting, “There was a bit of despair after the riots as we realised we had laid waste to our community.” This demonstrates how people must have felt as they realised more problems were to come now the community had to rebuild itself. On the one hand, Wheatle speaks of “burnt houses, burnt residences” describing how the Black communities’ homes had been damaged.

Pub scene at 'Atlantic' in Coldharbour Lane, 1987, Mike Hawthorne. Here customers are depicted drinking, talking, playing pool and listening to music about a year before the uprising.

On the other hand, specific establishments were destroyed as a result of their racist behaviours. For example, Wheatle describes a racist pub being burnt down by participants of the uprising, which had specifically refused to serve Black customers.

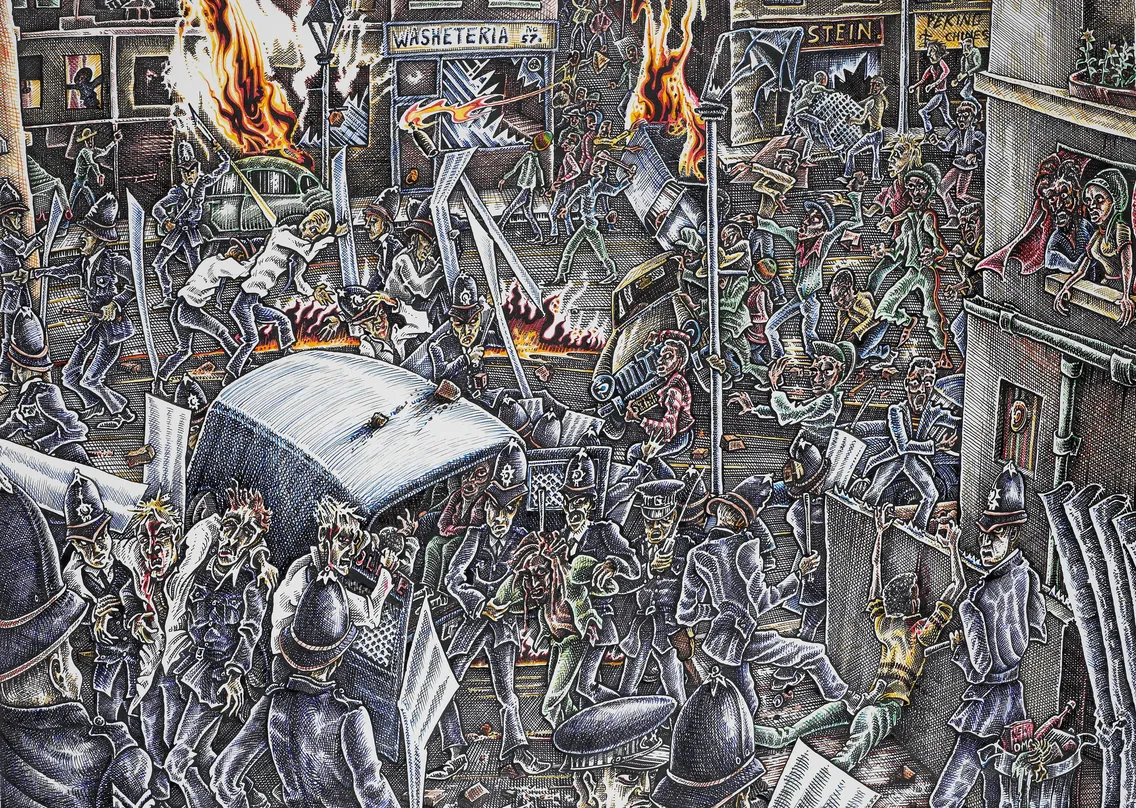

London Museum’s collection holds a drawing by Mike Hawthorne of the Atlantic pub on the corner of Brixton’s Atlantic Road and Coldharbour Lane, which was one of the first buildings to be attacked. A former customer recalled that “the white man who owned the pub would break your glass after you had finished using it.”

“There was a bit of despair…as we realised we had laid waste to our community”

Alex Wheatle

“Enough is enough…we are going to fight back”

The new landscape that emerged as a result of the uprising was a physical realisation of the struggle and trauma the Black community had faced both before and during the uprising. Yet, as Wheatle explains, this decimation of the area was valid and necessary in the struggle for equal rights and social justice. The pride the Black community felt towards Brixton is palpable in Wheatle’s words as he calls Brixton “our turf, our territory”. He explains that to some extent the damage to property held catharsis for the community as it showed they were no longer accepting racist behaviour. Wheatle elaborates on this, saying, “There was a bit of pride too…we are going to resist.” This was the point of the uprising: Black people refused to suffer injustices from the police and the state any longer.

The 2011 Brixton uprisings

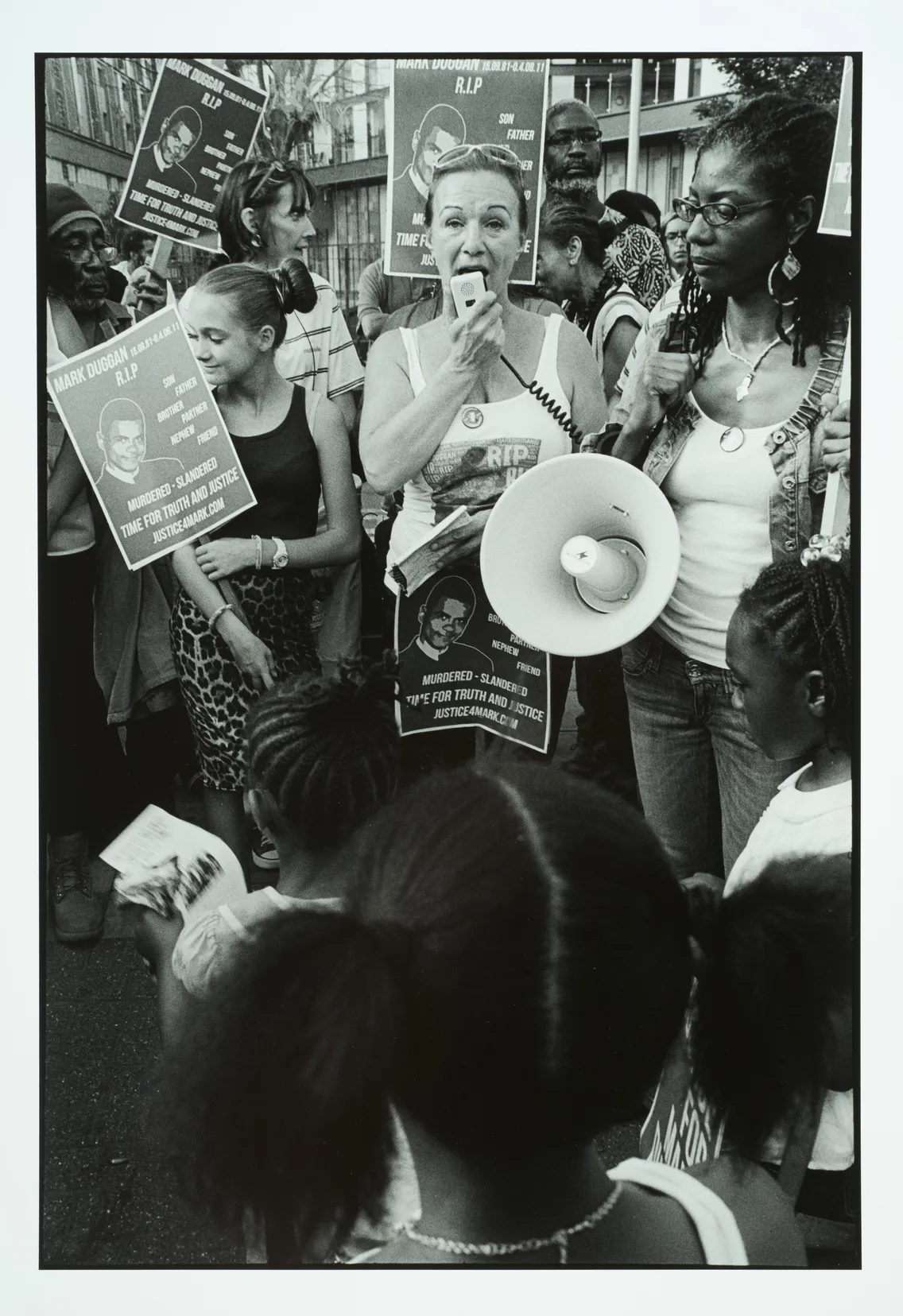

The 2011 uprisings were caused by the brutal police shooting of Mark Duggan, a 29-year-old Black man, who died due to this violence. The uprising first began in Tottenham, where Duggan was shot, then happened across London and spread in the UK. In 2011, physical damage again impacted Black communities. As a young teenager at this time, I remember seeing this both first and second hand. The news was flooded with coverage of damages incurred such as burning cars and buildings, looting, and violent clashes between protesters and the police. The media frequently lay the blame on Black people and did not take into account the systemic racism at the root of Mark Duggan’s shooting by the police and the unrest that followed. I was 13 years old. The upheaval of the uprising evoked strong emotions within me. I felt scared but the events also seemed intangible as I mainly saw them in the media. I felt confused but not in its simple definition of not having a basic understanding of the situation. My confusion was layered with questioning: Why couldn’t people who share my and my family’s identities be left alone? Be allowed to just exist without threat or attack from others? Why did there need to be this destruction for Black people’s voices to be heard?

In 2011, lots of shops were damaged or looted in areas where Black communities were located. This again emphasised the many layers of the physical damage in these uprisings and the way they reflect larger systemic issues. For example, some of the shops were attacked specifically because they represented large corporate structures whose interests and profits are rooted in exploitative capitalism. But again, this physical damage was happening on Black people’s doorstep, causing a direct impact on their lives. One of these impacts was highlighting to the rest of the country that the UK has a serious racism issue that must be dealt with.

Black Lives Matter, 2020

The Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020 took a different turn. They were caused by the police killing of George Floyd in the US and spread globally from there. Police officer Derek Chauvin killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck for 8 minutes 46 seconds, video footage of which was shared around the world. This uprising broke the trend of where the majority of physical impacts occurred. Instead of it happening in local Black and Brown communities, the majority of protests, at least regarding London, happened in central, politically important locations.

This actualised some of Wheatle’s sentiments in response to the Brixton uprising as he said, “We should’ve rioted in Whitehall”, and that the protests “should’ve been brought to the government’s doorstep”. In 2020, the defacing and destruction of statues, such as that of Robert Milligan in front of London Museum Docklands, was an especially powerful gesture seen in the UK, the US and elsewhere.

Robert Milligan's statue with protest placard and cloth before removal in June 2020.

Monuments tend to celebrate or remember the people they represent, and across the country, there are many statues of famous figures who held racist views or were perpetrators in the slave trade. When these statues were damaged it symbolised the Black community making themselves heard across the nation.

Ultimately the physical effects of these uprisings are multi-faceted, highlighting just how complex the road has been towards Black liberation from 1981 to now. The BLM protests emphasise a shift in racial dynamics across London and present the hope that we can continue on that path.

Jasmine Pierre is a Listening to London volunteer. The oral history extracts mentioned in this blog are from the ‘Brixton Riot’ collection (2009) ©London Museum.

Listening to London was a community-led research project making space for new interpretations of our Oral History collection at London Museum. This project was supported by The Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund – delivered by the Museums Association.